Volume 2 (2007) ISSN 1751-7788 back to volume contents print this article Alongside articles, the journal also publishes a number of 'fifth columns' - short and provocative pieces that might either frame/reference a number of the articles in the volume or raise issues relating to the scope and terms of musicology as a discipline. These 'fifth columns' should not be seen as 'editorials' |

||

| chemical bodies | ||

Paul Attinello Newcastle University |

||

I was educated in the unnamed capitol, or at least

the largest marketplace, of accelerating physical transformation: from

facelift to liposuction, Botox to retinoids, Prozac to street meth, Viagra to

steroids.[1] The culture of chemical and surgical alteration is increasingly ubiquitous,

and that ubiquity has been accelerating for decades - in the mid-1990s the

doctor at my Los Angeles HIV clinic continued giving me testosterone

injections even after blood tests showed that my levels had returned to

normal, because it would cheer me up and make me more like the opulently

healthy patients who, instead of shriveling and dying, strode grandly in and

out of his waiting room. A few years later, on having to start injections of

a medication that had strong depressive side effects, I was offered a range

of antidepressants to counter them, and then cautioned about the side effects

that would come from them - and of course we all have colleagues,

family, friends, taking antidepressants, antianxieties, and other behavior

modifiers. |

1 | |

All that is merely prehistory, of course, to the

chemically and biologically altered body: an accelerating biotech industry,

operating almost invisibly behind the medical industry, has already started

developing astonishingly powerful innovations of body, and mind,

modification. Though we are accustomed to using medical technology to correct

physical problems and (perceived) defects,[2] or to repair biochemistry and neurochemistry when it seems to go awry, the

border between correction and modification is already extremely porous;

cosmetic surgeries and Viagra are only occasionally used to help those

suffering from anything that can be considered a problem, and body

modification will soon, and increasingly, become a matter of taste.

Taste, desire, imagination, self-image: when gender construction, as well as

the body's energy, shape, and movement, are increasingly a matter of choice - as were tattoos and piercings during what may seem to our grandchildren the

primitive trends of the late twentieth century - the sheer fluidity and

intricacy of those choices will change everything. And everything will, of

course, include music - especially those genres which depend most heavily on

predictable identity/gender structures and emotions, such as the musical. |

2 | |

| A wonderful, disorienting, and faintly disturbing television commercial that may suggest the processes our imaginations will need to manage is Volkswagen's advertisement[3] for its Golf GTI, which played across European televisions in 2005. The copies available on YouTube are unfortunately fairly low-resolution, but they will give you an idea of what I mean. The dancer is 'Elsewhere', aka David Bernal (a Santa Ana lad who became famous for his breakdance skills in popping, locking and liquiding); the video was constructed by giving him a suit like Gene Kelly's original, choreographing him to move along the same directions and distances but in a completely different manner, and then digitally mapping the older actor's face onto the younger man's body. | 3 | |

|

||

This shimmering, popping body, all flexion and

energy, makes Haraway's cyborgs, and even Butler's performing bodies,[5] nearly, or

imminently, obsolete: increasingly the boxes that hold the body, and

of course gender, are dissolving, eliding - and naturally this has been

happening in waves of cultural change over decades, possibly centuries; but

once again the change is speeding up, the existing distinctions

disintegrating. This goes beyond the transformation of the body's image

through performance or cultural expectation, beyond the mechanical

transformation of the cyborg body: this is the body that functions as its own

processor, which may not be fully under the control of the person who seems

to be in charge of the brain. This is therefore beyond Butler, because even

performed gender implies a certain agency; this is beyond the way we can understand

agency, a body that has its own (ecstasy- or speed-fueled) movements and

flexibility, beyond anything that can be dictated by the person stuck

inside.... If at one time we could say that bodies did things, we couldn't pull

on our own strings, as it were - but now we can pull them, if still fairly

clumsily. When we can pull those strings increasingly well, increasingly

subtly, our control goes, and we may do things that are beyond our own

control. The chemical body is subject to changes that are invisible, unlike

the cyborg body; and the chemical body is not performed by any definable

agent of identity or personality, it is performed by chemicals - the

location of agency shifts, vanishes, behind a series of scrims, and we

literally don't know what we are doing. |

4 | |

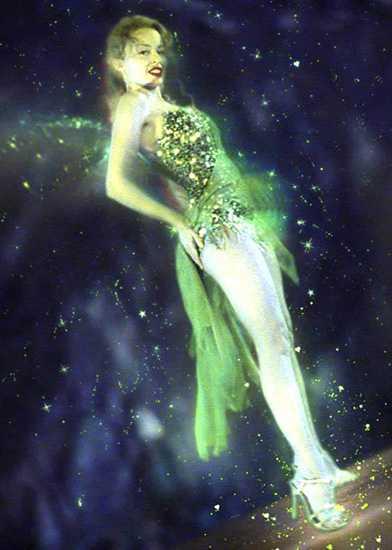

| Consider another video excerpt, the eerie and unforgettable transformation of Kylie Minogue into the Green Fairy in Baz Luhrmann's Moulin Rouge (2001). The CGI transformation of human into sprite ratchets up a step as her body twists and turns, her voice morphs to a masculine roar (overdubbed by Ozzy Osbourne), and she becomes a male/female figure of threatening, inhuman excitement, her body changing to represent the experience-altering wormwood of absinthe. | ||

|

5 | |

Of course, the moving images I am using as examples

are digital video transformations - and thus merely examples of contemporary

virtual technology, not of real chemicals altering real bodies.[7] But they

point forwards towards that which will be more disorienting than any virtual

reality - they suggest to us, they make us feel, the rush of changing

chemical compounds, things that will make our relations to dancing, to

singing, to romantic love, completely other.[8] That will

confound those of us who are accustomed to thinking of themselves as having

identities, or even those who have tried to move past identities to have only

experiences and desires - if even desires and experiences are contingent on

changing streams of chemistry, where do we locate our selves?... |

6 | |

And equally none of this really centers on the

musical: it merely hits it on a side bounce, as it were, as the musical has

not been culturally central for more than forty years now.[9] I've written

elsewhere that contemporary television musicals, such as those in Buffy

the Vampire Slayer, The Simpsons and South Park, as well as

those in Family Guy, Xena and other shows, normally begin by

displaying smug contempt for the old-fashioned, conformist, emotionally

predictable world of the musical; but then each is gradually overwhelmed by

the sheer power of musical-emotional technology, with its strong feelings

that trump any televised cynicism.[10] But what I'm trying to get at here, looking at these voluntary and

involuntary digital transformations of Gene Kelly, of Kylie Minogue, is a

next step that is waiting in the wings - if the body's shape and sound can be

changed, how will we recognize the leading lady? If the body's energy and

flexibility can be changed, how can we still be impressed by the virtuosic

dancing body? |

7 | |

So, as many of the outré theoretical pyrotechnics

of the past forty years reappear, not in the mind, but in the body: body-altering

drugs, bodies as simulacra, bodies without organs, because they have

dissolved in rapidly changing chemical systems: we finally admit to ourselves

that we have always been puppets of organic chemistry.... And, as Rent (1996) suggests, through its junkie heroine who just likes to "feel good",

and then tries to hide with grandiose and apparently sincere ensemble

numbers: if the love interest is chemically altering her- or him-self - how can we believe in the romance, in any kind of love, in any experience

at all; how can we take the emotions of the music or the plot seriously

enough to care? |

8 | |

We will struggle to find our balance in a world

where our very perceptions are endlessly modified, change upon change until

we can't remember where we started; but for another generation this may

simply become their reality: and the strong theories of the twentieth

century, the culture of suspicion, which is based on the importance of hidden

meanings, will continue to dissolve; as everything becomes equally,

endlessly, internally-because-chemically, suspicious... |

9 | |

[1] An earlier version of this was read, at

Mitchell Morris' invitation, for a symposium on 'The American Musical on Stage

and Screen' at UCLA in October 2007. I am grateful to Merrie Snell for her

technical help. [2] This is, of course, a process that is already heavily culturally mediated - consider for instance the now wide range of writings on transgendered bodies, from Michel Foucault's I, Herculine Barbin... (New York: Pantheon, 1980) to Jay Prosser's Second Skins: the Body Narratives of Transsexuality (Columbia University Press, 1998). [3] This clip is available on Youtube at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r1q98m7qJ8g. [4] Another interesting dance video based on Mint Royale's remix, oriented towards a different but equally fantastic imaginative universe, is available on Youtube at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3cscZeUqxxM. [5] Donna Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: the Reinvention of Nature (London: Free Association Books, 1991); Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990). Instead of reading these books, which in a way reflect cultural change in the 1980s and 1990s, perhaps we should be reading Fen Montaigne's Medicine by Design: the Practice and Promise of Biomedical Engineering (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006) and Veikko Launis & Juha Räikkä, editors, Genetic Democracy: Philosophical Perspectives (Vienna: Springer Verlag, 2008). [6] Though drugs today, despite the mass of ancient jokes rooted in 1960s ideas of being 'mind-altering', are no longer really about the mind at all - speed, so absurdly cheap and impossible to stamp out in a host of small labs scattered across poor suburbs, doesn't really have any effect on the imagination; it merely, well, speeds things up - the body's experience and effect is modified, such that experience becomes contingent, suspect, unreal. Crack and cocaine, ecstasy - and the heroin that floats through the plot of Rent, distorting all its relationships: drugs and pharmaceuticals, all adding even more complex tangents to the chemical body.... In this context, it is worth considering a range of popular non-fiction discussions over the past decade, such as those that followed on Peter Kramer's Listening to Prozac: a Psychiatrist Explores Antidepressant Drugs and the Remaking of the Self (New York: Viking Press, 1993; revised edition 1997). This is the book that invented the term, quite apposite to this discussion, "cosmetic psychopharmacology." [7] Such digital transformations will continue to transform film and the way we read it in coming years - frequently anticipated in science fiction, of which Connie Willis' version in Remake (New York: Bantam, 1995) best emphasizes how such bodies as Gene Kelly's, and Kylie Minogue's, become ever more malleable products rather than representations of selves. [8] This change has been imagined in a vast number of science fiction scenarios, notably the novels of William Gibson, Greg Egan, and K. W. Jeter (whose extraordinarily nasty gender reminaginings in the infamous Dr. Adder (1984) may have inspired David Cronenberg's film Dead Ringers (1988)). An interesting and recent transference to the world of fairy tales appears in John Connolly's The Book of Lost Things (London: Hodder, 2006), especially the surgeries of chapters 15-17. [9] Which is not meant as some sort of Lebrechtian complaint about yet another 'death' of the musical: but the musical has based its existence on stable planes of culture (which is why it has been in such huge trouble since those plates shifted tectonically during the 1960s). Under these circumstances, musicals have become the raw material for newly produced broadcast materials - much as classical music becomes raw material for new popular music (for which consider Robert Fink's 'Elvis Everywhere', American Music, vol. 16 no. 2 (Summer 1998), 135-79). These days, the musical always carves out a contingent, largely borrowed, aesthetically and culturally rather pathetic corner for itself, even in a global Internet culture which increasingly allows niche audiences to thrive for practically anything; so the question then becomes, what distortions and desperate attempts at crowd-pleasing will keep it alive in twenty years? [10] Paul Attinello, 'Rock, Television, Paper, Musicals, Scissors: Buffy, The Simpsons, and Parody', in Sounds of the Slayer: Music and Silence in Buffy and Angel (edited by Paul Attinello and Vanessa Knights), to be published by Ashgate in 2009. Admittedly, High School Musical (2006), with its sequel and imitators, seems to reverse this trend - frankly I remain somewhat bemused by its success: is it really possible that cultural/aesthetic trends can move so radically backwards, that such an emotionally retro pastiche can become popular with a young audience? But perhaps the sheer unexpectedness of High School Musical's style is what makes it a success: like many musicals since Hair (1968), it may be a niche trend, not much more culturally significant than a Tamagochi pet. |

||