|

Piety and Populism: Tippett's A Child of

Our Time and the Oratorio Genre

|

|

|

|

|

Anne Marshman |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The oratorio emerged from the religious setting of Filippo Neri's prayer meetings in sixteenth-century Rome where the popular tunes of laude spirituali helped 'draw, with a sweet deception, the sinners to the holy exercises of the Oratory'.[1] This combination of piety and populism was to become a recurrent feature of the oratorio genre over the next four centuries and can also be found in Michael Tippett's A Child of Our Time (1939-41) with its mix of biblical references, African-American spirituals, dance and jazz influences. Religious affiliations were underscored at the work's premiere in London's Adelphi Theatre on Sunday 19 March 1944 through its adherence to the oratorio tradition of Lenten performance.[2] This essay focuses on A Child of Our Time's religious and popular elements and the semantic significance of their interactions both within the immediate context of the oratorio genre and in terms of the premiere's broader social context. The performance is proposed as a site for the licensed critique of ecclesiastical authority during World War Two and, as such, reflective of socio-political currents at the time. The interpretation presented here offers a counterbalance to the overwhelming orientation in the existing literature on A Child of Our Time towards the score and Tippett's intentions.[3] Although there is widespread criticism in these studies of musical and textual inconsistencies and formal imbalances, at the same time the work's diverse intertextual allusions are carefully traced to Tippett's biography and writings, resulting in a unified interpretation that, as I argue in this essay, belies inherent pluralities. My aim here is to remove the spotlight from the composer and to explore hermeneutic alternatives for A Child of Our Time's intertextuality and disjunctions. I draw on Mikhail Bakhtin's theory of heteroglossia to emphasise tangible bonds between musical and textual voices and their contexts of creation and reception. This approach differs to other musicological applications of Bakhtin's literary and linguistic theories to musical works, which focus almost unanimously on musical and textual voices as functions of a score whose meaning is determined according to composer intent.[4] That the work of Bakhtin, who places such emphasis on the semantic dependence of language and art on context, has been applied in this way further highlights musicology's tenacious preoccupation with the score and the composer's voice. Also borrowed in this essay is Bakhtin's concept of carnival to enable a fresh interpretation of what have been described by Tippett and others as the work's 'universal qualities'. |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Christian Churches in Britain at the Time of the 1944 Premiere |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In his study of British society from 1914-1945, John Stevenson identifies among the period's 'most significant features', the 'decline of organized religion, judged both in terms of the allegiance and membership of the Christian churches and their role as arbiters of public conventions and private morality'.[5] While continuing expansion marks the period leading up to the First World War, the war years witnessed a significant slump, attributed largely to 'the effects of the horror and carnage of the war'.[6] Though there was some recovery during the 1920s, a downfall was once more recorded in the 1930s and the onset of World War Two only 'exacerbated this trend'.[7] |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Besides the disillusionment engendered by war, a burgeoning leisure industry fostered by continued urbanisation, technological advancement and a more affluent society was another major factor in the diminishing importance of religion for many Britons.[8] The new diversions of cinema, dance, radio and an expanding popular press were all aimed at wooing the emerging masses.[9] These entertainments were 'more exciting and fashionable' than those previously provided by the Churches and, in many cases, 'as respect for the Sabbath declined, they were increasingly in direct conflict with religion'.[10] Indeed, a 1945 report commissioned by Archbishop William Temple (Archbishop of York, 1929-1942; Archbishop of Canterbury, 1942-44) remarks on what was seen at the time as 'a wholesale drift from organized religion'.[11] A central message of the report was 'the decline of any real sense in which Christianity was a matter of daily reference for most Englishmen'.[12] |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

However, the Church's place in society was not clear-cut (due to the period's trend towards ecumenism, the term Church is taken here to encompass Roman Catholic, Anglican and Free Churches).[13] In 1945, Britain still had 'legislation in areas such as drink, sex and Sunday observance which reflected a Christian outlook'.[14] The Church was also influential in its 'opposition to divorce, artificial birth control, obscenity, drink, [and] homosexuality'. Despite signs that public views on these subjects were changing, 'resistance by the churches could often prove decisive', as is evidenced by their 'crucial' role in the 1936 abdication of Edward VIII who wanted a divorced woman to become his Queen.[15] |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Church's social influence was called into play by the British government during World War Two, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

appear[ing] to reinforce the old notion of the interdependence of religion and civil order in England. Broadcasts and speeches by public men included Christian references and often tended to identify national political and social arrangements with divine will.[16] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By invoking the name of God, the state endowed the war with the moral imperative of a 'just war', which was reinforced by the Church's supplication to God for support in the allied cause through national days of prayer.[17] Archbishop Temple justified the war in terms of its objective to: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

preserve a civilization that has never of course, been completely Christian, but has been very deeply influenced by the Christian view of life; and we are fighting to keep open the possibility of a still more truly Christian civilization in the future.[18] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

But this pro-war stance created tensions within the Church. Pacifist Christians protested against the war's immorality, drawing a distinction between Jesus' message of peace in the New Testament and Jehovah's vows of vengeance in the Old. Activists meanwhile argued that the two could not, in accordance with the principle of the Trinity, be so conveniently separated.[19] Indeed, Bishop Hensley Henson explained pacifism as 'a misunderstanding of Christ's teaching and an unbalanced humanitarian sentimentalism'.[20] In a 1944 Sunday Express article, 'It is Time for Reprisals!', another clergy member, D. R. Davies, called for blood. An eye for an eye was evidently nowhere near enough for Davies who demanded the death of ten Germans for each English person killed.[21] Pacifists' appeals to the Church to petition against Churchill's 'area' bombing of German civilian targets were met by Archbishop Temple's denial of any knowledge of such attacks. But, as Alan Wilkinson points out, area bombing was 'well known to, and popular with, many of the British population', making this denial somewhat implausible.[22] By 1943 Temple had changed his mind on the matter, writing in a letter that 'the one thing that is certainly wrong is to fight ineffectively'.[23] The disillusionment of pacifists with this type of attitude within the Church led many to leave the institution altogether.[24] |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Child of Our Time's intertextuality and discontinuities, within the traditionally Christian site of the oratorio genre, mirror the complexities and challenges that characterise the Church's experience during this pivotal period. In the context of the 1944 London premiere, these features bear witness to 'a society in transition, still sustaining a Christian view on some things, but riddled with inconsistencies'.[25] Underpinning this line of argument are the oratorio's credentials as a religious genre characterised by the mixing of pious and popular elements. Before examining the work and its premiere, it will, therefore, be useful to briefly outline certain relevant aspects of the genre's history and to establish the continuing British perception in 1944 of the oratorio's alignment with Christianity. |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Piety, Populism and the Oratorio Genre |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Like the laude spirituali whose vernacular texts and music helped Neri in his 'fishing of souls' (as he once described the spiritual exercises of his oratory in a report to the Pope), secular influences also contributed to the appeal of the emerging oratorio in the seventeenth century.[26] By the 1660s, when the oratorio was firmly established in Italy, its operatic musical styles made it an increasingly popular entertainment in secular settings, such as the palaces of the nobility, during Lent when theatres were closed. Striking a balance between the pious and the popular, however, was not always easy. The combination precipitated varying degrees of public consternation and Church censorship from the time of the genre's Italian birth through several strands of development in different countries, but this side of the oratorio's history is frequently understated in the literature.[27] Howard Smither's classification, for instance, of Handel's English oratorio (the sub-genre from which A Child of Our Time is directly descended) as a 'concert genre more closely related to the theatre than the church' suggests that the oratorio's religious roots had simply been eclipsed by popular characteristics.[28] But, as Ruth Smith argues, the situation was not so straightforward. She shows that the religious messages of Handel's libretti were more significant and their juxtaposition alongside secular musical styles far more disconcerting for eighteenth-century listeners than such categorisation allows.[29] There was a prevailing belief that music for a religious purpose 'should sound different' from music for the theatre and the oratorio's 'mingling of generic elements' was seen by many to undermine important moral and aesthetic values.[30] Contemporary sources attest to a wide-ranging disorientation and displeasure provoked by Handel's generic mixing and, when his oratorios' popularity continued after his death, so did the controversy.[31] |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Despite continuing apprehensions, the oratorio (particularly those by Handel and, especially, Messiah) went on to achieve a 'semi-sacred status' in Victorian England.[32] This was largely through the agencies of the choral societies who viewed the singing of oratorios as a 'boon to the improvement of morals and church services', [33] and through regular cathedral performances of oratorios at the choral festivals that swarmed the country.[34] The oratorio was also immensely popular in nineteenth-century Britain, which, as Nigel Burton remarks, was dominated 'not by opera, as in the rest of Europe, but by the oratorio'.[35] The Crystal Palace's monumental Handel Festivals might have appealed to Neri's populist bent. In the 1870s a standard of 3000 singers and 500 instrumentalists could be expected, with the audience peaking in 1882 at 87, 769.[36] By this time, as George Bernard Shaw notes with customary wryness, Handel himself had become a 'sacred institution': |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

When his Messiah is performed, the audience stands up, as if in church, while the Hallelujah chorus is being sung. It is the nearest sensation to the elevation of the Host known to English Protestants.[37] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Victorian institutions of choral festival and choral society, with their core repertoire of oratorios, remained central to British musical life until the commencement of World War Two.[38] While some continental oratorios in the twentieth century moved away from Judeo-Christian themes (for example, Hanns Eisler's and Bertolt Brecht's Die Massnahme, 1930, Honegger's Cris du monde, 1931, and Hindemith's Das Unaufhrliche, 1931), most remained ethically or spiritually oriented.[39] In England, however, A Child of Our Time's major forerunners, by Edward Elgar (The Dream of Gerontius, 1900, The Apostles, 1903, The Kingdom, 1906), Ralph Vaughan Williams (Sancta Civitas, 1923-5) and William Walton (Belshazzar's Feast, 1931) maintained a traditional religious emphasis. Moreover, a survey of newspapers and music journals between 1935 and 1944 demonstrates a continuing perception of the oratorio as a Christian genre. In 1935, a pageant performance of Elijah was criticised, for example, because of the 'lasciviousness in drama' that accompanied 'Mendelssohn's most virginal music', while a 1943 Messiah in Westminster Abbey 'impressed' The Musical Times' reviewer 'because the right music was heard in the right place'.[40] During a period when Church attendance was declining it was even remarked that Handel's popular oratorios succeeded where organised religion had failed to disseminate Christian messages: 'to sing the choruses is to know at least [the Bible's] outline'.[41] The programming of oratorios around the ecclesiastical calendar helped reinforce the genre's pious status and concert listings of the period attest to its continuing popularity. As one American visitor who attended A Child of Our Time's premiere remarked, 'oratorio is a form for which the English have a distinct preference, as witness the success of Elgar's Dream of Gerontius (three scheduled hearings in two months), or Walton's Belshazzar's Feast'.[42] |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pious and Popular Heteroglossia in A Child of Our Time |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Besides its designation in the score as an oratorio, A Child of Our Time fulfils several conventions of the genre, including biblical references, biblical style language and the formal design of Bach's Passions with their narrative recitatives, contemplative arias and descriptive choruses. Tippett's work is also aligned with Handel's archetypal English oratorio, Messiah, through its tri-partite structure, fugal choruses and a direct intertextual reference to the opening of Part II (see below). These and other references and generic conventions in A Child of Our Time can be understood as musical and textual heteroglossia. The term literally means 'many voices', but in Bakhtinian theory it has vital social connotations relating to the inseparability of language and literature from their contexts of production and reception.[43] We speak in heteroglossia every day choosing the most appropriate vocabulary, phrasing and inflection for where we are and to whom we speak. Even 'an illiterate peasant' leading an uncomplicated life 'miles away from any urban center, naively immersed in an unmoving and for him unshakable everyday world', employs a range of heteroglossia (social languages) for various purposes, such as, praying in church, singing work songs, speaking with family and friends, or addressing a town official.[44] This understanding of language's propensity to absorb and project contexts from which it emerges and in which it functions underpins all Bakhtinian literary and linguistic theory and yet it is constantly overlooked in the musicological literature. |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pious and popular heteroglossia are represented in A Child of Our Time's generic codings, intertextual references and stylistic allusions. A striking feature of the work is the manner in which these voices collide and engage, reflecting the complex nature of the Church's place in British society during World War Two. The ideological struggle within the institution is mirrored in Numbers 21 to 24 where the precedence of violence in the Bible, cited by activists as justification for the Church's support for the war, is recalled ('Go down Moses', No. 21): |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

'Thus spake the Lord,' bold Moses said, Let my people go, 'If not, I'll smite your first-born dead,' Let my people go. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Number 22, immediately following Jehovah's murderous threat, the 'child' of Tippett's title sings: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

My dreams are all shattered in a ghastly reality. The wild beating of my heart is stilled: day by day. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Even if listeners did not register Tippett's allusion to pacifist poet, Wilfred Owen's 'Strange Meeting', which mourns the never-to-be-lived life of a dead soldier,[45] the boy's fate must have conjured for the premiere audience images of England's sons who at that moment lay dead or dying on Europe's battlefields. This scene is brought still closer to home by the boy's grieving mother (No. 23): |

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

My heart aches in unending pain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And the ensuing commentary (No. 24): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Men's hearts are heavy: they cry for peace. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When Christians questioned how God could allow the war's atrocities, their bewilderment was often met by the Church's traditional platitude that one must simply trust in God no matter how mysterious his ways might seem.[46] Other Christians, including theologian Nathanial Micklem (chaplain and later Principal of Oxford's Mansfield College), explained the war as divine retribution: |

13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

When we ponder the acknowledged moral decay in France, the repudiation of Christianity in Germany, the secularism that dominated the pre-war age here as in Europe, the social injustices, the godlessness, the flaunting of wickedness, we might more wisely ask how we could not believe in God, if He did not bring such rottenness down in destruction.[47] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

F. A. Cockin, canon of St. Paul's Cathedral agreed: 'this is the kind of world you have asked for; and nothing, not even divine omnipotence, can save you from getting it'.[48] And to be sure, the subdued tango that underlies the song of the 'ordinary man' (No. 6) hints at suppressed passions and yearnings ('I am caught between my desires and their frustration'), undermining the oratorio's pious pedigree just as Europe's iniquities compromised the Church's social influence. The tango was known at the time for its sexually provocative movements and 'restrained eroticism'[49] and, with the foxtrot (evoked in No. 7), it was one of the most popular dances of the jazz and dance-craze that had swept Britain between the wars.[50] Supported by the work's jazzy syncopations and inflections (especially in Nos. 23 and 27) and spirituals, these dances represent, within their oratorio context, the expanding popular culture identified as a major factor in the fading importance of religion in Britons' lives. |

14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Both pious and popular voices are heard in the oratorio's five African-American spirituals. The question of whether these songs have been successfully integrated with Tippett's twentieth-century idiom has received much critical and scholarly attention. Echoing through the literature are Tippett's reasons for their inclusion. Searching for a substitute for Bach's Passion chorales, he saw the spiritual as a 'modern universal musical symbol', believing 'that in England or America everyone would be moved' in the same way.[51] I suggest, however, that this is doubtful, given the songs' complex social, cultural and political associations in 1944. Spirituals were familiar in Britain as popular songs, made famous largely through the performances, recordings and broadcasts by the well-known singer, actor and son of a slave, Paul Robeson, who was among Britain's 1937 top ten best-selling singers.[52] A Child of Our Time's spirituals relate to the plight of the songs' creators ('Nobody knows the trouble I see, Lord', No. 16; 'Go down Moses, 'way down in Egypt land, Tell old Pharaoh, to let my people go', No. 21) and their yearning for release from oppression ('Steal away to Jesus', No. 8; 'O by and by, I'm going to lay down my heavy load', No. 25; 'Deep river, Lord, I want to cross over into camp-ground', No. 30). They also suggest the speech idiom associated with the slaves, for example, in 'Steal Away': |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The trumpet sounds within-a my soul, I han't got long to stay here. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and in 'Deep River': |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I want to cross over into camp-ground, O, chillun! O, don't you want to go |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Besides recalling this historical struggle, the spirituals' jazzy syncopations might also have brought to mind the contemporary racial injustices in America, which were often reported in the British press.[53] These implications are reinforced by the word 'lynchings' in Number 4. The spirituals' references to the New and Old Testament are reminders not only of the persecution of the ancient Hebrew slaves (for example, 'Go Down Moses'), but also, given the 1944 performance's political context, of their modern descendents in Hitler's Europe (the knowledge of which was, by this time, widespread). |

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Like the oratorio, religious and popular elements were a part of the spiritual genre's inception but, unlike the liturgical Lutheran chorale (the generic parallel drawn by Tippett), the songs are not a straightforward Christian genre. The slaves' religion was not a direct adoption of their white masters' faith, but a hybrid of Christian and African traditions. While owners encouraged slaves' conversion to Christianity, hoping that the authoritative figure of God and visions of heaven would inspire obedience, the slaves were more interested in God's promise of liberation for their Old Testament Hebrew counterparts.[54] As Lawrence Levine points out, 'there was always a latent and symbolic element of protest in the slave's religious songs which frequently became overt and explicit'.[55] Consequently, 'Go Down Moses', which can be heard as much as a protest song of freedom as a protestation of the slaves' white masters' religion, was prohibited on many plantations.[56] 'Nobody Knows' (No. 16) is characterised by Cornel West as a call for 'social solidarity - "to drive Old Satan away" '.[57] In fact, spiritual lyrics were often intended as secret codes. 'Steal Away' (No. 8) would signal, for instance, the arrival of a guide to assist slaves in escape bids. Although it is unlikely that 1944 listeners would have been aware of the spirituals' subversive roots, their frequently enigmatic texts deemed 'unintelligible' by nineteenth-century whites still manage to convey a sense of otherness that resists complete semantic coercion and defies the songs' depiction as 'universal'.[58] (Samuel Floyd, Jr., applies to African-American music the concept of signifyin(g), 'a complex rhetorical device', identified by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. in black literature.[59] According to Floyd, in order to unlock its codes, black music and its occurrence in white art require an approach that is informed by African-American culture. In slave songs signifyin(g) is part of 'the surreptitious communication so necessary to slave culture'.[60]) |

17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The bodily movements, including 'exaggerated arm, shoulder, hip and leg movement', and moans and shouts that typically accompanied the spirituals' syncopations were frowned upon by nineteenth-century whites who saw them as 'pagan' and 'vulgar'.[61] Unauthorised prayer meetings where such habits were likely to go unchecked were forbidden. There is a sense of Western containment in the spirituals' musical adaptations for white audiences and their further transformation in A Child of Our Time through Tippett's immaculate high-art settings and contrapuntal textures.[62] Zora Neale Hurston notes fundamental differences between 'genuine Negro spirituals' and 'Neo-Spirituals' sung for white audiences. In her 1934 essay, she emphasises the physicality of the former: |

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Negro singing and formal speech are breathy. The audible breathing is part of the performance [. . .]. This is, of course, the very antithesis of white vocal art. European singing is considered good when each syllable floats out on a column of air, seeming not to have any mechanics at all.[63] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hurston describes the 'jagged harmony', lack of regard for precise pitch and ensemble, 'shifting keys and broken time' and the all-important 'dance-possible rhythm' of the spirituals.[64] Traces of this physicality and 'dance-possible' rhythms remain in Tippett's syncopated settings, supporting the suggestions of dance and popular culture evoked by the tango and foxtrot (Nos. 6 and 7). Their impact is vitiated, however, by the classical performance style that is part of the oratorio tradition, and by intricate counterpoint (the choir divides into up to eight parts) in 'Nobody Knows' (No. 16) and 'Go Down Moses' (No. 21). |

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

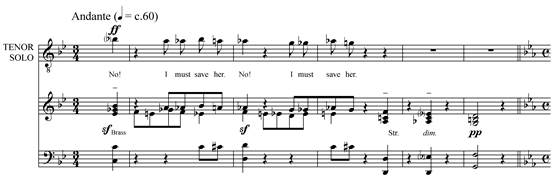

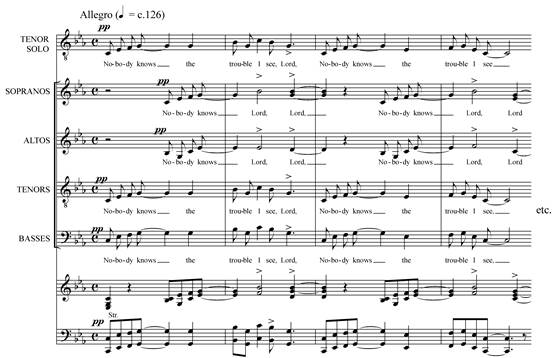

Writing in 1944, Wilfred Mellers questions Tippett's explanation of the spirituals as universal, because 'the persecuted negro is too topical and local a symbol'.[65] Compounding this sense of social and cultural distance and semantic independence explored above is the actual sound of the spirituals against Tippett's musical idiom, despite his widely discussed attempt to integrate the songs by using their characteristic intervals of minor 3rd, perfect 5th and minor 7th throughout the oratorio. Indeed, this unifying gesture becomes all but redundant when the spirituals' melodic and harmonic predictability are heard amidst Tippett's non-repetitive, chromatic and harmonically non-functional language. This aural disparity is apparent in the progression from the declamatory quartet (No. 15) to the tuneful simplicity of 'Nobody Knows' (No. 16). Notwithstanding some textual continuity between Number 15's struggle and the piteousness of 'Nobody Knows', in Tippett's setting the spiritual's up-beat tempo (crotchet = c. 126) and syncopations seem almost placatingly jaunty in reply to the quartet's tortured anguish: |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

No. 15 Boy: Though men hunt me like an animal, I will defy the world to reach you. Aunt: Have patience. Throw not your life away in futile sacrifice. Uncle: You are as one against all. Accept the impotence of your humanity. Boy: No! I must save her. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Given the scarcity of traditional cadences throughout the work and the quartet's tonal instability, the final G major chord's cadential lead-in to the spiritual's opening C minor has the tone of an outdated clich (see Fig. 1). Indeed, the spirituals' traditional melody and harmony seem anachronistic in their new context. Perhaps at the work's first performance in war-ravaged London, given the decreasing membership of, and growing disillusionment with the Church (and its well-used platitudes referred to above), the spirituals' Christian resonances might also have seemed anachronistic. Reflecting the complexity of the work's heteroglossia and the Church's position, it is also reasonable to expect that some might have perceived the spirituals as a comforting refuge in a disintegrating world. |

21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1: Transition from No. 15 to No. 16. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adding to this complexity, the spirituals also bore political overtones in 1944. In the 1930s Robeson's high-profile activism was becoming stronger and he regularly sang the songs in support of left-wing causes, including the International Peace Campaign, the Basque Children's Committee, the Food for Republican Spain Campaign, the Unemployed Workers' Movement and the League for the Boycott of Aggressor Nations.[66] Suzanne Robinson traces the spirituals' leftist associations to the composer's politics. She also points to Eisler and Alan Bush's use of oratorios as vehicles for Communist propaganda and communal singing (for example, Eisler's and Brecht's Die Massnahme and Bush's and Randall Swingler's adaptation of Handel's Belshazzar).[67] Although the composer's intentions are beyond the concerns of this essay, Robinson's research also sheds light on his work's potential meaning for the premiere audience. Stevenson paints an impressive picture of the powerful 'quasi-religious certainty' of British Marxism, believing that it 'should be considered in the same league as religion as a focus of belief and activity'.[68] From this perspective, the intrusion of the voice of the left in a generic space normally dedicated to the espousal of Christian beliefs, symbolises another challenge to religion in an increasingly secular society (the Communist Party of Great Britain's notable increase from 2 555 members in 1930 to 18 000 in 1939, led the 1930s to be dubbed the 'Red Decade').[69] This antagonism between what T. S. Eliot described in 1934 as the 'mutually exclusive' doctrines of Communism and Christianity was not restricted to the ideological, but also manifested more materially in the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) where the Catholic Church sided with the Nationalist rebels while the CPGB supported the Republicans (its members comprising more than half of the British volunteers who died in the fighting). [70] |

22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Besides being represented by popular styles discussed above, the emerging masses of the period also find voice in colloquialisms ('dole' and 'no-man's-land' in No. 13) and straightforward utterances in crowd scenes (for example, 'Away with them! Curse them! Kill them', No. 11, and 'Burn down their houses! Beat in their heads!', No. 19).[71] Contrasting with these heteroglossia are the sophisticated intellectual tones of intricate contrapuntal writing, Tippett's non-repetitive idiom and references to works by Owen, Carl Jung and T. S. Eliot.[72] Indeed, one of the most startling disjunctions in A Child of Our Time is the incongruity between these voices and Tippett's stated desire for universal relevance. Besides his description of the spirituals as 'universal' he also hoped that through the tenor's 'tango' aria (No. 6) 'the ordinary man listening [. . .] can feel himself truly expressed and understood':[73] |

23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I have no money for my bread; I have no gift for my love. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Directly following this line is an allusion to Part 1 of Eliot's Murder in the Cathedral: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I am caught between my desires and their frustration as between the hammer and the anvil. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Even if Tippett's 'ordinary man' (who couldn't afford a loaf of bread let alone the price of a concert ticket) somehow found himself at the oratorio's premiere, it is unlikely that he would have deciphered the meaning of this and other elusive references. As Ian Kemp points out, the libretto is in need of 'extended exegesis before it can be understood'.[74] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discontinuities between popular and intellectual elements in Tippett's score mirror the unbreachable gaps of Britain's hierarchical society. In 1946-48 one half of the country's total wealth was in the hands of one per cent of the population, meanwhile the humiliation of unemployment (there were consistently one million unemployed between 1920 and 1940), the 'dole' and the means test exacerbated the gulf between rich and poor.[75] It was those educated at public schools and the prestigious universities of Oxford and Cambridge who held an overwhelming majority of senior civil service, army, judiciary, government ministry and Church positions.[76] The gaps between Britain's social classes are reflected in disjunctions between music and text in the crowd scene of Number 19's fugal chorus. Just as the educated elite ran the country and directed the war (with the Church's moral support), so the traditional formal structure of this strict fugue can be heard at work, organising the antagonised throngs: |

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Burn down their houses! Beat in their heads! Break them in pieces on the wheel! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The fugue resounds with the established authority of state and Church. The incongruity between the text's baying for blood and the music's fugal aloofness reflects the inequalities of a class system where some by virtue of their aristocratic birth managed to stay clear of the worst fighting.[77] The regimented formal scheme imposes order over the vernacular fury of the less privileged whose emotions are harnessed and whose sons are delivered in orderly fashion to the front line. |

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Populism and Universalism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tippett's wish for universal relevance was typical of many middle-class artists, including W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and C. Day Lewis, who wished to speak to and for the emerging masses. That their ambitious objectives remained largely unrealised, Spender ascribes to an inability to comprehend the true nature of the masses to which none of them actually belonged: |

26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The writers in the thirties are often sneered at because they were middle-class youths with public school and posh university backgrounds who sought to adopt a proletarian point of view. Up to a point this sneer is justified. They were ill-equipped to address a working-class audience, and were not serious in their efforts to do so.[78] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Although Tippett's intentions are not the topic of this essay (his middle-class, public school upbringing links him to these writers), conflicts between A Child of Our Time's vernacular and intellectual heteroglossia do mirror what Spender describes as a broader 'middle-class crise de conscience': |

27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The capitalist system [...] which was incapable of employing the workers, or, if they were unemployed, preventing them from almost starving was the same system that supported the cultivated leisured class of those whose aesthetic values seemed to have no connection with politics and social conditions.[79] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Despite the apparent futility of Tippett's bid to reach the masses there is another kind of universal significance that can be attributed to A Child of Our Time via Bakhtin's concept of carnival. |

28 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Universalism and the Popular Carnival Festival |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bakhtin invokes the rituals and imagery of the medieval carnival festival as metaphors for stylistic and generic traits in literature, particularly the novel and especially the novels of Franois Rabelais. Carnival is a festival of and for the people. Bakhtin likens its popular celebrations to the novel's stylistic and formal flexibility whereas the stricter criteria of 'high' genres such as lyric poetry and epic are compared to the more rigid formalities and 'official and serious tone of medieval ecclesiastical and feudal culture'.[80] Carnival entails a 'temporary liberation from the prevailing truth and the established order' when official notions of beauty, decorum and manners are challenged and those who are usually coerced into silence are free to speak.[81] In Rabelais' novels and in carnival, hierarchies of daily life are humorously challenged and ruthlessly subverted through irony and satire, and heteroglossia from all sections of society come together and are given voice. Bakhtin also identifies elements of carnival in the novels of Fyodor Dostoevsky (although he acknowledges the 'reduced laughter' of a novel like Crime and Punishment), with their purposeful combination of diverse social heteroglossia that enable realistic portrayals of contemporary society.[82] In Dostoevsky's novels as in carnival 'everyone is an active participant, everyone communes in the carnival act'.[83] A Child of Our Time similarly gives musical and verbal representation to a range of social heteroglossia of the times from which it emerged and in which it was first heard. The perspectives of pacifist and activist, leftist and conservative, black and white, Christian, Jew and sceptic, working-, middle-, and ruling-classes are all represented. Like the celebrations of carnival this type of artistic multi-voicedness is characterised by Bakhtin 'as something universal, representing all the people'.[84] |

29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

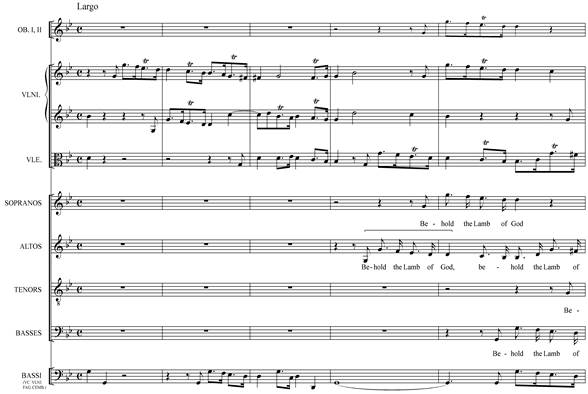

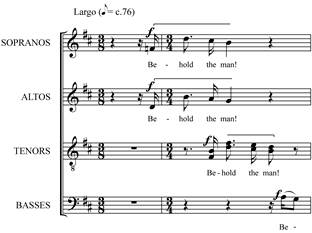

Adding currency to A Child of Our Time's carnival character are instances of irony and boisterous insurrection. Under carnival law bishops and kings are mercilessly uncrowned and official doctrines and ideologies interrogated. At the opening of Part II there is a reference to exactly the same place in Handel's Messiah, which depicts Jesus' birth: |

30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Behold the Lamb of God that taketh away the sin of the world. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In A Child of Our Time this becomes, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A star rises in mid-winter [a reference to the Bethlehem star] Behold the man! The scapegoat! The child of our time. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This reference has previously been dismissed as a flaw in Tippett's libretto, an example of his inconsistent treatment of Christian symbolism.[85] But this twisting of Messiah, described by Smither as 'the most famous English oratorio in history' (which most people in the 1944 audience would have heard and possibly sung),[86] represents a carnivalistic de-crowning of the Son of God. The fact that the music accompanying 'Behold the man' imitates Messiah rhythmically and melodically vividly underlines the reference (see Fig. 2a and Fig. 2b). In the same way that the king of carnival is ritually de-crowned, Jesus the Lamb of God is replaced by a hapless scapegoat, an ordinary 'child of our time' who ultimately meets his demise at the hands of God himself: 'God overpowered him - the child of our time' (No. 28). As Kemp points out, during the period of the premiere 'this was a startling and even blasphemous statement'.[87] Nevertheless, its impact is mitigated by Kemp's interpretation of 'God' according to the composer's Jungian philosophy, that is, as the archetypal power of the collective unconscious.[88] (This interpretation is not self-evident from the score. It was first offered by Tippett in the lead-up to the 1944 premiere and has influenced all scholarly reception from that time until the present day.)[89] 1944 listeners unversed in Jungian psychology would not, however, have heard this line in such terms. Given the Church's public wartime stance, it is difficult to ignore that its God was, indeed, implicated in the deadly deeds of war. |

31 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

According to Bakhtin the parodic crowning and subsequent decrowning of the carnival king occurs in 'the zone of maximally familiar and crude contact' through 'the removal of an object from the distanced plane, the destruction of epic distance'. By transporting the epic of Jesus' birth into the contemporary sphere of 'our time' it becomes available for cross-examination in familiar territory where one can 'turn it upside down, inside out, peer at it from above and below, break open its external shell, look into its center, doubt it'.[90] This carnivalistic skepticism is pertinent to the mood of religious disillusionment during the war. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2a: Messiah. No. 19. Chorus. 'Behold the Lamb of God'. Opening measures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2b: A Child of Our Time. No. 9. Chorus. 'Behold the man' (beginning in sopranos and altos; continued in tenors). Measures 22-23 (chorus only). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conclusion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Despite its subversive rituals and frequent targeting of religious laws, carnival was actually the brainchild of the Catholic Church, intended as a form of sanctioned release prior to the prohibitions of Lent. But carnival overstepped its seasonal boundaries in 1944. Its popular voice sounded forth that Sunday in Lent, echoing through the gaps and crevices prised open by A Child of Our Time's irreconcilable disjunctions that, as I have argued above, have not been fully accounted for by considerations of the score and composer intent. A Child of Our Time's diverse heteroglossia, like the voices of carnival, give representation to a whole range of worldviews and not just the oratorio's official Christian voice. In the context of the 1944 premiere, within the traditionally religious site of the oratorio, pious and popular voices reflect the Church's competition with secular culture and the growing threat of religious scepticism. During a period when secularity and popular culture were both on the rise, the vernacular voice once seconded via the oratorio into the Church's service assumed greater potency and independence. At A Child of Our Time's premiere these popular strains spilled out of the oratorio, resonating in sympathy with social and cultural voices of the time as they surged their way towards an increasingly secular post-war landscape. [1] Oratio Griffi, dedication to Filippo Neri, in G. F. Anerio, Teatro armonico spirituale di madrigali (Rome, 1619). As cited in Howard E. Smither, A History of the Oratorio, 4 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977-2000), 1: 122. Smither identifies the lauda spirituale as the oratorio’s main antecedent. [2] Following the Oxford English Dictionary definition of ‘pious’, where appropriate, I use the term, interchangeably with ‘religious’. ‘Pious, adj.’. OED Online, http://www.oed.com.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/view/Entry/144365?redirectedFrom=pious (5 October 2011). [3] Including, but not limited to, Meirion Bowen, Michael Tippett (London: Robson, 1997); Kenneth Gloag, Tippett: A Child of Our Time (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999); Ian Kemp, Tippett: The Composer and His Music (London: Eulenburg, 1984), 149-179; Jeffrey Poland, ‘Michael Tippett’s A Child of Our Time: An Oratorio for Our Time’, Choral Journal Vol. 34 (1994), 9-14; Suzanne Robinson, ‘The Pattern from the Palimpsest: The Influence of T. S. Eliot on Michael Tippett’, Ph.D. diss., University of Melbourne, 1990; Suzanne Robinson, ‘From Agitprop to Parable: A Prolegomenon to A Child of Our Time’, in Robinson, Suzanne (ed.), Michael Tippett: Music and Literature (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002), 78-121; Stuart Sillars, ‘A Child of Our Time’, in British Romantic Art and the Second World War (London: Macmillan, 1991), 124-41; Arnold Whittall, The Music of Britten and Tippett (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 72-74. I examine Tippett’s influence on the premiere’s critical reception and subsequent scholarship in, Anne Marshman, ‘Pre-emptive Hermeneutics: Tippett’s Early Influence on A Child of Our Time’s Reception’, Context: Journal of Music Research Vols. 29 & 30 (2005), 17-29. [4] Including, David Clarke, ‘ “Shall we . . .? Affirm!” The Ironic and the Sublime in The Mask of Time’, in The Music and Thought of Michael Tippett (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 147-205; Anthony Gritten, ‘Stravinsky’s Voices’, Ph.D. diss., Cambridge University, 1999; Kristian Hibberd, ‘Shostakovich and Bakhtin: A Critical Investigation of the Late Works (1974-75)’, Ph.D. diss., University of London, 2005); Kevin Korsyn, ‘Beyond Privileged Contexts: Intertextuality, Influence, and Dialogue’, in Cook, Nicholas and Mark Everist (eds.), Rethinking Music (Oxford University Press, 1999), 55-72; Kevin Korsyn, ‘Brahms Research and Aesthetic Ideology’, Music Analysis Vol. 12 (1993), 89-103; Nicholas Peter McKay, ‘A Semiotic Evaluation of Musical Meaning in the Works of Igor Stravinsky’, Ph.D. diss., University of Durham, 1998; Carl Wiens, ‘Igor Stravinsky and Agon’, Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 1997. For a discussion of the literature, see Anne Marshman, ‘Music as Dialogue: Bakhtin’s Model Applied to Tippett’s A Child of Our Time’, Ph.D. diss., University of Melbourne, 2006, 2-13. [5] John Stevenson, British Society: 1914-1945 (London: Allen Lane, 1984), 356. [6] Ibid., 357. [7] Alan D. Gilbert, The Making of Post-Christian Britain: A History of the Secularization of Modern Society (London: Longman, 1980), 77. [8] Andrew Thorpe, Britain in the 1930s: The Deceptive Decade (Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1992), 103. [9] ‘Masses’ denotes here ‘a very large number’ of people, an understanding which, according to Raymond Williams, has ‘predominated’ in the twentieth century. Implications of social class only apply in that the ‘masses’ can be differentiated from that which is viewed as culturally elite. [Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (London: Fontana, 1983), 195-196.] Williams relates this sense of the term to ‘mass production’, ‘mass market’ and ‘mass culture’. The term used in this essay is ‘popular culture’, which denotes ‘products produced primarily for entertainment rather than intrinsic worth [...] in response to mass taste’. Daniel Bell, ‘Mass Culture’, in Bullock, Alan, Oliver Stallybrass, and Stephen Trombley (eds.), The Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought, rev. ed., (London: Fontana, 1988). [10] Thorpe, Britain, 103. [11] Towards the Conversion of England. (London, 1945), 3. As cited in E. R. Norman, Church and Society in England 1770-1970 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1976), 394. [12] Norman, Church and Society, 394. [13] While certain tensions between churches were still apparent during WW II, previous decades had seen a trend towards ecumenism. Stevenson, British Society, 366. Hoover’s discussion of British churches during WW II also reflects this trend. A. J. Hoover, God, Britain, and Hitler in World War II: The View of the British Clergy, 1939-1945 (Connecticut: Praeger, 1999). [14] Stevenson, British Society, 370. [15] Ibid. [16] Norman, Church and Society, 393. [17] Hoover, God, 14-15. [18] William Temple, Towards a Christian Order (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1942), 8. As cited in Hoover, God, 98. [19] Hoover, God, 25-37. [20] Alan Wilkinson, Dissent or Conform? War, Peace and the English Churches 1900-1945 (London: SCM Press, 1986), 234. [21] As cited in Wilkinson, Dissent or Conform?, 266-267. [22] Wilkinson, Dissent or Conform?, 265-266. [23] F. S. Temple (ed.), William Temple: Some Lambeth Letters (Oxford University Press, 1963), 102. As cited in Wilkinson, Dissent or Conform?, 266. [24] Wilkinson, Dissent or Conform?, 289. [25] Norman, Church and Society, 394. [26] Giovanni Marciano, Memori historiche della Congregatione dell’Oratorio (Naples, 1693-1702). As cited in Smither, Oratorio, 1: 52. [27] Marshman, ‘Music as Dialogue’, 77-103. [28] Smither, Oratorio, 2: 197. [29] Ruth Smith, Handel’s Oratorios and Eighteenth-Century Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 44-46. [30] Ibid., 44-45. [31] See, for example, Otto Erich Deutsch, Handel: A Documentary Biography (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1955), 300-1; 338; 339; 657; 773; Charles Edward McGuire, Elgar’s Oratorios: The Creation of an Epic Narrative (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002), 24-27; Smither, Oratorio, 3: 199. [32] McGuire, Elgar’s Oratorios, 19-20. [33] Ibid. [34] William Weber, ‘The Music Festival and the Oratorio Tradition’, in The Rise of Musical Classics in Eighteenth-Century England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992), 103-142. [35] Nigel Burton, ‘Oratorios and Cantatas’, in Temperley, Nicholas (ed.), Music in Britain: The Romantic Age: 1800-1914, Vol. 5 (London: Athlone, 1981), 214. [36] Robert Manson Myers, Handel’s Messiah: A Touchstone of Taste (New York: Macmillan, 1948), 243. [37] George Bernard Shaw, Shaw’s Music: The Complete Musical Criticism, ed. Dan H. Lawrence, 3 vols. (London: Max Reinhardt, 1981), 3: 638-9. [38] Smither, Oratorio, 4: 276. [39] Ibid., 4: 631. [40] ‘Elijah Production at the Albert Hall’, The Times 12 Feb. 1935, 12; ‘London Concerts’, The Musical Times Vol. 84, No. 1204 (June, 1943), 191. [41] ‘Mr. Handel’, The Times 23 Feb. 1935, 13. [42] Gail Kubik, ‘London Letter’, Modern Music Vol. 21 (1944), 240-243: 242. [43] Mikhail Bakhtin, ‘Discourse in the Novel’, in Michael Holquist (ed.), The Dialogic Imagination, tr. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 263. [44] Ibid., 293-6. [45] Michael Tippett, Tippett on Music, ed. Bowen, Meirion (Oxford: Clarendon, 1998), 160. [46] Hoover, God, 9. [47] Nathaniel Micklem, Europe’s Own Book (London: Morrison & Gibb, 1944), 48. As cited in Hoover, God, 10. [48] F. A. Cockin, ‘The Judgment of God’, in Sampson, Ashley (ed.), This War and Christian Ethics: A Symposium (London: Blackwell, 1940), 6. As cited in Hoover, God, 10. [49] Marta E. Savigliano, ‘Whiny Ruffians and Rebellious Broads: Tango as a Spectacle of Eroticized Social Tension’, Theatre Journal Vol. 47 (1995), 83-104: 84. [50] Derek Scott, ‘The “Jazz Age”’, in Stephen Banfield (ed.), The Blackwell History of Music in Britain: The Twentieth Century (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995), 57-78: 59. Ian Kemp describes Number 7 as a ‘dimly perceived foxtrot’. Kemp, Tippett, 172. [51] Tippett, Tippett, 112. [52] Martin Bauml Duberman, Paul Robeson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988), 226. [53] A major feature notes, for example, 134 lynchings in the South from 1927 to 1936. Clark Foreman and Thomas Jesse Jones, ‘The Negro in American Life: A Serious Minority Problem’, The Times 8 June 1939, 40. [54] Lawrence W. Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 44-50. [55] Ibid., 51. [56] Richard Newman, Go Down Moses: A Celebration of the African-American Spiritual (New York: Clarkson Potter, 1998), 68. [57] Cornel West, foreword, in Richard Newman, Go Down, Moses: A Celebration of the African-American Spiritual (New York: Clarkson Potter, 1998), 9-17: 16. [58] Richard Crawford et al., ‘United States of America’, Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com (July 16, 2011). [59] Henry Louis Gates, Jr., The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 52. [60] Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., ‘Ring Shout! Literary Studies, Historical Studies, and Black Music Inquiry’, in Gena Dagel Caponi (ed.), Signifyin(g), Sanctifyin’, and Slam Dunking (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 133-156: 140-141. [61] Crawford, ‘United States’. [62] For a discussion of race relations represented in A Child of Our Time’s spirituals, see Marshman, ‘Music as Dialogue’, 161-166. [63] Zora Neale Hurston, ‘Spirituals and Neo-Spirituals’, in Cunard, Nancy (ed.), Negro: An Anthology, (New York: Continuum, 1970), 224. [64] Ibid., 225. [65] W. H. Mellers, ‘Two Generations of English Music’, Scrutiny 12 (Autumn, 1944): 268-9. [66] Duberman, Paul Robeson, 222; Robinson, ‘From Agitprop’, 84. [67] Ibid., 90-92. [68] Stevenson, British Society, 371. [69] Thorpe, Britain, 42. [70] T. S. Eliot, ‘Religious Drama and the Church’, Rep 1 (1934) 4-5. As cited in Robinson, ‘From Agitprop’, 101; Thorpe, Britain 48. [71] See note 9. [72] For a list of intertextual references see, Marshman, Appendix A, ‘Music as Dialogue’. [73] Tippett, Tippett, 128. [74] Kemp, Tippett, 164. [75] Stevenson, British Society, 330. [76] Ibid., 349-352. [77] Madeleine Beard, English Landed Society in the Twentieth Century (London: Routledge, 1989), 76. [78] Stephen Spender, The Thirties and After (London: Macmillan, 1978), 23. [79] Ibid., 22. [80] Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, tr. Hélène Iswolsky (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 4. [81] Ibid., 10. [82] Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, tr. and ed. Caryl Emmerson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), 166. [83] Ibid., 122-3. [84] Bakhtin, Rabelais, 19. [85] Kemp, Tippett, 160; Robinson, ‘Pattern’, 68-9. [86] Smither, Oratorio, 3: 216. This claim is suggested by concert listings and reviews from 1944, for example, in The Observer, The Daily Telegraph and Morning Post, The Times, and The Musical Times, which indicate the enormous challenge of ascertaining how many performances (by professionals, amateurs, schools, colleges, etc.) occurred in and around London that year. Other signs of Messiah’s ubiquity are not hard to find. It is named in The Musical Times, for example, as the only work recognisable to the ‘common listener’ (along with, possibly, ‘ “the” Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto’) and, in January and February 1944, two separate reviewers wished that choirs would give the work ‘a rest’. Anne Medley, ‘ “Musical Appreciation” and the Common Listener’, The Musical Times, 85, No. 1214 (Apr., 1944), pp. 105-107: 105; W. R. Anderson, ‘Round About Radio’, The Musical Times, Vol. 85, No. 1212 (Feb., 1944), pp. 46-48: 47; ‘Royal Choral Society: Messiah’, The Times 3 Jan. 1944, p. 8. [87] Kemp, Tippett, 163. [88] Ibid., 155-7. [89] Marshman, ‘Pre-emptive Hermeneutics’, 22. [90] Bakhtin, ‘Discourse’, 23.

|

32 |