|

||

|

|

The Sublime Space of Male Masochism in Elvis Costello's 'When I Was Cruel No. 2' |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anna-Elena Pääkkölä |

|

|

|

University of Turku |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction: Queer sounds and spaces... and masochism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Approaching the theme of 'queer sounds and spaces' from the point of view of male masochism and cultural music research offers three different windows through which music can be interpreted. First of all, 'queerness' is a concept all queer scholars must define at the onset. While I hold the core issues of queer studies to reside within LGBT themes, I argue throughout this article that queerness can also be studied in reference to broader concepts as well; here, the much debated practice of sexual masochism. Secondly, 'queer sounds' create a specific queer atmosphere in a song or a piece of music. While this concept is difficult to pin down, queer sounds in music include elements of music, voices, and sound effects that together contribute to the atmosphere of a piece of music, and to make this atmosphere 'queer' is to rely on unconventional musical solutions (within genre, lyrics, arrangement, or any other aspect of the musical piece). Thirdly, 'queer spaces' in music can span from physical spaces to musical spaces, atmospheres, or as I will argue in this article, a space created by the music itself, both auditively and lyrically. |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sadomasochism has been a heated topic of debate in feminist and queer thinking for at least the past 30 years. While some arguments focus on whether or not sadomasochism (SM for short) repeats and dangerously eroticizes existing gender power imbalances, other approaches focus on SM's potential in subverting heteronormative sexualities and gender roles. The question still remains unresolved whether or not SM is queer. In this article, I demonstrate how male masochism (seen here as a 'sub-genre' of sadomasochism despite their epistemological differences) as a musical performance can be considered queer, but also why this alliance between queerness and masochistic sexuality can be a forced one.[1] By this, I do not mean to argue that masochism or sadomasochism are by default queer, but demonstrate certain affinities between queer theories and masochism as well as their differences. While the argument for sadomasochism having the potential for sexualising and normalising gendered violence or, perhaps nowadays especially, sexual harassment, it is crucial to look more closely at specific instances and ascertain their queer potential, or alternatively, their lack of it. |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Of course, claims of gendered violence in SM relationships can be more easily contested when the dominant party is a woman and the submissive is a man. An easy suggestion here would be to read the relationship as having queer potential for reassigning new gender roles to the participants: a dominant woman could be considered as empowered; a submissive man could be considered as embracing weakness without risking his masculinity. The claim that historically male masochism starts from Baron of Sacher-Masoch's works in the 19th century could suggest that the queer potential is not clear-cut after all. In this article, I read Elvis Costello's song 'When I Was Cruel No. 2' (2002) through the concepts of 'male masochism' and 'queerness'. In doing so, I suggest that certain queer spaces can be produced within songs, where matters of sexuality can be easily explored, but this is often done without risking the disapproval of heteronormative society or, indeed, the artist's audience. The concept of 'queer space', then, is phantasmatical, an escapist and, perhaps, utopian one, when it is found within the temporal space of a particular song. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

'When I Was Cruel No. 2', released in 2002 as the fourth track of the album When I Was Cruel, is an indie rock song by Elvis Costello. In this article, I read the song as presenting a queer space of alternative masculinity through Gillez Deleuze's and Leo Bersani's theories of male masochism.[2] I discuss Costello's song through three lenses: queer temporality, feminist musicology, and melancholia. All these angles address aspects of male masochism (understood here as a sexual preference), the eroticism produced in the song, and their queer potential. In doing this I also demonstrate how sadomasochism and male masochism can create a musical space of queerness through the use of queer-encoded sounds. The article draws from my PhD dissertation,[3] where I research SM aesthetics through such methodologies as cultural musicology,[4] queer musicology,[5] and close reading.[6] |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Although the song can be heard as cynical, Costello himself has noted that it includes a glimmer of hope: |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

It's a true song, a true telling of the tension between your disdain for people who wield and abuse power, and your instinct to forgive people. (...) When you're young, you tend to distance yourself from the responsibility to consider the humanity in people you despise. Just making them demons is too easy, is what I'm saying.[7] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Analysing the song, I demonstrate how 'making them demons is too easy' is not only about forgiving, but also about sexualising. Indeed, on closer examination, the cynicism of the song seems to coexist with a distinct feeling of eroticism and cruelty encoded in the lyrics as well as the instruments accompanying them. My analysis, like Elvis Costello's song, includes also the darker hues of masochistic aesthetics, involving such elements as neosurrealism, the queer death drive, nostalgia, temporality, and manipulation. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spaces: queer temporality and the death drive in repetitive music |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

'When I Was Cruel No. 2' has been constructed through the compositional technique of sampling. The most noticeable aspect of the song's backing track is a female voice uttering the syllable 'un'. The original loop of this 'un' vocal is sampled from the Italian singer Mina's song, 'Un Bacio É Troppo Poco' (1965, composed by Bruno Canfora and Antonio Amurri). The loop makes the song into a seven-minute, swaying, quasi-Latin song, on top of which Costello adds guitars, electric bass, and various other instruments. The song's narrative, while quite oblique, is a neosurreal portrayal of a high-society wedding, depicted as a dystopic, plastic society where money and status count more than affection. The narrator-singer, 'I', is paying close attention to the bride, who seems to have a personal relationship with the song's 'I', but the nature of that relationship is left unclear. In this reading, I lean on Simon Frith's concept of 'character as style',[8] where the singer-songwriter performs the song through the mediation of characters, who in turn represent a particular style or a feeling. In my reading, the characters represent ideals or archetypes in SM relationships: more specifically those of the cruel lady (bride or 'she') and the male masochist ('I'). |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The repetitive pattern of the 'Un Bacio É Troppo Poco' loop in Costello's song creates a specific temporality which suggests, I will argue, a corresponding masochistic-erotic atmosphere in the song which could be regarded as spatially encoded. Repetition in music has been widely discussed in musicology, at times recognised as pleasurable when it comes to listening to music and creating it, especially when looping is involved.[9] The constant repetition of the looped Mina song snippet can be discussed through subjective temporality, for example. While Deleuze has written extensively about repetition as a phenomenon, he pays special attention to repetition in Sacher-Masoch's work.[10] This creates a window of possibility for investigating a new form of subjective/surreal temporality in Costello's song, and relating it to Masochian aesthetics and eroticism. |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Deleuze observes that fantasy, surrender, and service are at the heart of the sexual gratification in Sacher-Masoch's view, even (or perhaps, especially) if it is delayed beyond one's control.[11] The plotline of Venus in Furs (first published in 1870) consists of conversations and persuasion between the lovers, fantastical owner/slave situations including those of punishment, and the protagonist's musings about his situation as a slave and fond thoughts of the mistress. Detailed descriptions of sex scenes are avoided, but sex exists in Sacher-Masoch's works as a mode of intimacy, not pornography.[12] Deleuze describes this appositely as 'a state of waiting; the masochist experience waiting in its pure form'.[13] Elements of time and waiting add to the (sublime/painful) pleasure of the masochistic experience, and the uncertainty of when the waiting will end also heightens the experience. In this way, the suspension and active manipulation of subjective time becomes the climactic 'moment', in the word's widest possible sense, of Sacher-Masoch's text. This happens with the suspension of the tortured body (bondage), but also the suspension of the body of the dominating party as an idea, a picture or a statue, which is then fetishised by the masochistic character in his imagination. This happens quite similarly in the song's chorus: 'Look at her now / she's started to yawn / she looks like she was born to it' (1:30-1:49). Her image is suspended in its yawning state, implying either tiredness or boredom, but slowness in either case. Suspension of small moments becomes the pleasure of repetition, sublimated through the unreachability of the original utterance as well as its temporal manipulation. |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

When the object of the masochistic fantasy, the dominant cruel woman, is suspended, in time (as in a work of art or a song) or as a fantasy image (imagined or absent), we begin to perceive both the fetish value of the masochistic dream and the gender-specific fantasies that Sacher-Masoch presents to us. The sampled repetition of Mina's song would suggest, in the Deleuzian sense, not simply a sadistic will to control, manipulate, and dominate the feminine essence in Costello's song, but a masochistic repetition used to create suspense. In many musical forms (minimalism or house music, for example), the repetition of small, distinct musical gestures can construct a sense of flow, which slowly starts to mould perceptions of subjective time.[14 This can create a sense of losing grasp of mathematically divided clock time. Perhaps this is especially true of some electronic dance music forms, where dancing to the music is as important as listening to it, producing a feeling of 'losing yourself' as well as losing your sense of time in the music. In this way, repetitive music could be akin to Bersani's concept of sexual masochism as a spatial concept: the mind creates an alternate space where repetitive music creates an alternative temporality and impells the mind and body to move, and accordingly, the music can be experienced as libidinally, sublimely satisfying.[15] The masochist's imagination creates a space, albeit phantasmatic, where his sexuality dictates every aspect of the experience. The sexual fantasy becomes self-sustaining, even creating the illusion of dominating, in turn, the male masochist himself. Costello's repetition of Mina's song becomes a fetishistic fantasy, where the omnipresence of Mina's voice is made into an artefact outside of linear time, suspended. This surpasses perceptions of mathematical time and becomes a dream-like state of masochistic waiting.[16] Also location, movement, and (masochistic) identification become fragmented, suspended and disjointed with social expectations. |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The historicity of the masochistic temporality is relevant when considering Costello's song. It is built on existing songs and works: Mina's song, Satie's Gnossienne No. 1, a textual quote from Wagner's wedding march from Lohengrin, ABBA's 'Dancing Queen' (1976), and Costello's song, 'When I Was Cruel' (2002b). The historically varied references are mashed up into a new work, where they create a sense of the past echoing in the present of the song. According to Deleuze, however, the nostalgia created here is not enough for masochistic aesthetics: the repetition apparent in the death drive is |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

a synthesis of time - a 'transcendental' synthesis. It is at once repetition of before, during and after, that is to say it is a constitution in time of the past, the present and even the future.[17] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If we treat the sampled quotations of songs and classical works as echoes from the past, and Costello's 'Cruel No. 2' as the present, the future tense of this song is in the sampling itself. Every eighth beat, as we hear Mina's voice, we start to anticipate it, we enjoy knowing it will be there throughout the song, we start to fetishize it, and we are reassured by every repetition. In short, the coexistent past, present and future represent the new, masochistic temporality, all three temporal categories converging in a single song. Costello maintains also a feeling of failure and melancholia. It is not, therefore, exactly a joyous depiction of a high-society wedding or a simple sexualised fantasy of a self-actualised, successful woman moving up in society through marriage. The bitterness of the song refuses to yield to the masochistic joys of subjective temporality, but this bitterness also contributes to the pleasure, resulting in the presence of traumatic Freudian death drive repetition in the song. Indeed, some musicologists have discussed certain forms of repetitive music as invoking the death drive.[18] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When Sigmund Freud was studying what in his mind were deviant sexualities, he was especially troubled by masochism, as it seemed to go against what he called the pleasure principle or life instict,[19] seeking out pain and gaining pleasure within it. Freud hence developed the concept of the death instinct or the death drive, 'the vitalising of inanimate matter, and [...] the reinstatement of lifelessness'.[20] The pleasure principle (Eros) and the death drive (Thanatos) are both presumably present in every human's psyche and are in constant struggle with each other. Building upon these theories, queer theorist Lee Edelman has posited the notion of the 'queer death drive'.[21] As the queer lifestyle is not biologically capable of fulfilling society's mandate for reproduction, the queer lifestyle could be seen, in essence, to be more in accordance with the death drive rather than the life instinct. Queerness inhabits the margins and is the property of the outsiders of 'productive' society. Lacan calls this 'jouissance', 'a movement beyond the pleasure principle, beyond the distinctions of pleasure and pain, a violent passage beyond the bounds of identity, meaning, and law'.[22] Whereas neither Lacan nor Edelman discuss the death drive in reference to sexual masochism, Leo Bersani sees masochism and the death drive as integrated in the very core of sexuality.[23] In this way, we can listen for the death drive in music and read it also within the economy of sexualised/eroticised pleasure. |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

As mentioned above, the death drive has been discussed in musicology through, for example, the concept of repetitive music. Indeed, repetitive music can be a depiction of the experience of increasing tension, or by extension, sexual titillation. Stan Hawkins analyses house music, another groove- and beat based music form, as pleasurable because of its escapist nature and its potential for ritualizing social interaction, submitting to the experience of community in a certain type of mysticism.[24] 'Losing yourself' in the beat creates a space of ecstatic, masochistic enjoyment where the sense of self, as well as the listener's moving, dancing body, become part of some larger entity. This sonic experience 'offers the dancer/listener access to a polymorphous experience of the body whose pleasure is not confined in simple gender terms'.[25] John Richardson theorises repetition in music as having three distinct roles: creating suspense, creating groove, and creating a distancing effect.[26] These effects work in different ways, but should not be understood as mutually exclusive. |

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

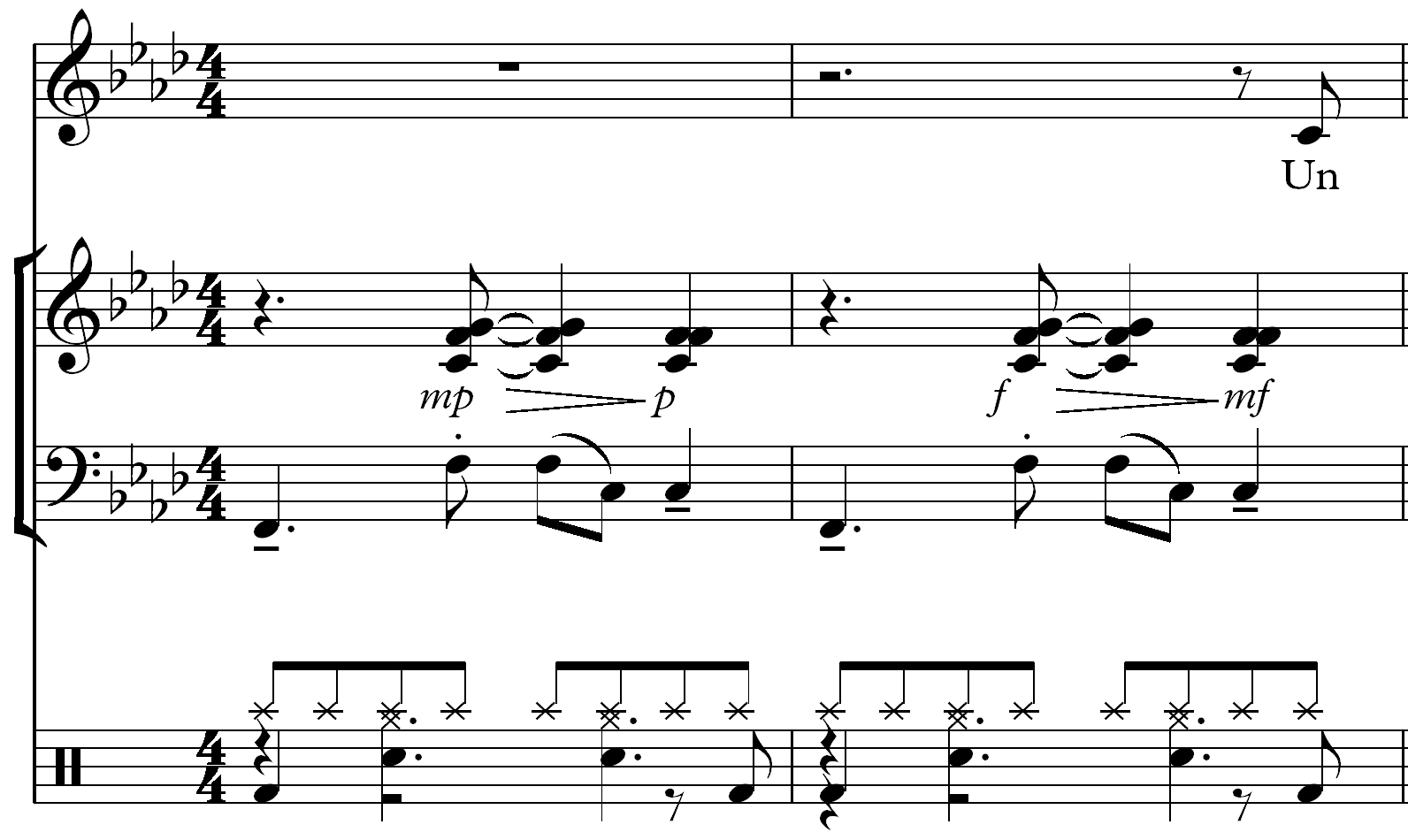

In Costello's song, suspense is created through subjective temporality, discussed at length above. Groove and distancing effects are also discernible in the song. The repetitive loop of 'When I Was Cruel No. 2' creates the general groove of the song. (See example 1 for a reduction.) The rhythm created with the drum set is a stable 4/4 beat with the first beat emphasised by the bass drum, while the snare drum and hi-hat accentuate the second beat, and another accent falls between the third and fourth beats. The bass alternates between the tonic and octave-tonic falling to the dominant, creating the juxtaposed rhythm of a dotted quarter note, three eight notes and a quarter tone, accentuating the first, third and fourth beat. In this way, the general groove is syncopated, but there are two syncopated rhythmic patterns running against each other: that of the bass and guitar (3:3:2/8), and that of the snare drum and hi-hat (2:3:3/8). Together, they both destabilise and reaffirm the general 4/4 beat, creating a flowing, quasi-Latin (tango-like) polyrhythm, driven forward by the pull of the suspended guitar's 'sigh motive' (a suspended ninth note descending to tonic, mixed first in the background, then foregrounded). Costello adds to the feeling of sway by adding guitar chords on top of the F minor loop, mainly the fluctuation between E flat major and F minor (the seventh and tonic of the Aeolian minor scale) during the verses of the song. The overall effect is of stability and swaying, giving the groove a danceable and rocking feel. Combined with Mina's robotic repetition of the last eighth note of the two-bar loop (discussed in more detail in the next section), the atmosphere is sensualised, the repetition is transformed into flow, the mechanical into dance. |

13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Example 1: Sampled rhythm and groove reduction of Mina's 'Un Bacio É Troppo Poco', creating 'When I Was Cruel No. 2' loop. Mina's voice, guitar and the 'sigh motive', bass, drums. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This loop creates a groove that is negotiated in Costello's layered guitars and bass. While Costello adds chord changes to the loop (especially to the choruses with the vibraphone), the looped song serves also as a constant pedal point, keeping the song firmly rooted in F minor. While the stationary groove and the fixed tonality of the song remain reassuringly the same, some suspense is created also by the guitar motif. The loop also creates a distancing effect, suggesting a cynical hue. The original, clear-cut loop becomes distorted by adding Costello's grimy, sustained, heavily reverbed guitars. These are in turn juxtaposed with the pristine yet echoed vibraphone. Laden with sounds that rewrite the mood of the song from a clear wedding ballad to a more gritty one, and Costello's melancholic rendering of dry vocals, Costello's nihilistic depiction of musical death drive-like pleasure opts for repetition and suspension rather than developing the song or the loop further, or establishing a release of tension. |

14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

What makes the use of this particular sample a form of queer masochism is an argument that can be supported in several ways. Firstly, the use of the sample does not promote a relaxed atmosphere, but a strained one that is, nevertheless, sexually laden. Secondly, the interplay between the loop and the added instruments creates both tension and continuity, grimy cynicism and appreciation of the repeated loop, but the tension never reaches climax or release. Thirdly, Mina's omnipresent voice creates sensuality, both vocal and embodied, through the groove in the loop. This sensuality is both resented and sexualised in a queerly masochistic way. This third factor will be discussed at length in the next section. What is queered here, then, is the notion of male heterosexuality into masochism, and the resulting romantic feelings into melancholy. Before exploring this idea further, the position of the Lady in the masochistic dream as well as the bride of the song deserve some attention. |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Queer sounds: The omnipresent Lady and neosurrealism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Having considered how queer spaces are created through the use of repetition and queer temporalities, I now turn to the question of queer sounds in the song. A general concern in (sado)masochistic heterosexual relationships concerns gendered power and the inequalities between the parties in such a relationship. It remains to be discussed what kinds of femininities are created in the male masochistic fantasy of this song, and whether these might be considered queer. In this section, I look to the relationship between the song's 'I' and the woman, how both are created musically, and how their positions are queered through their auditive realisations. |

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

'When I Was Cruel No. 2' depicts a wedding where the first person narrator of the song is keeping a keen eye, or rather, a keen ear, on the bride. The woman, always referred to as 'she', is described through multisensory means: the smell of her perfume, the fabrics of her dress, and her dancing body in motion. It is implied that she may also be somewhat under the influence of alcohol. The trademark 'sneering' quality of Costello's voice implies a certain disdain towards the lady who is the subject of the song. Musically, Costello has employed Mina's song to vocally represent the depicted feminine entity. It is easy to understand why 'Bacio' would contribute to Costello's ambivalent depiction of the bride: the original lyrics tell of a coquettish woman pondering if just one kiss is enough to know if she loves 'you'. This is not however the extent to which the feminine is portrayed in the song: Costello constructs her using instrumentation and musical allusions. |

17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

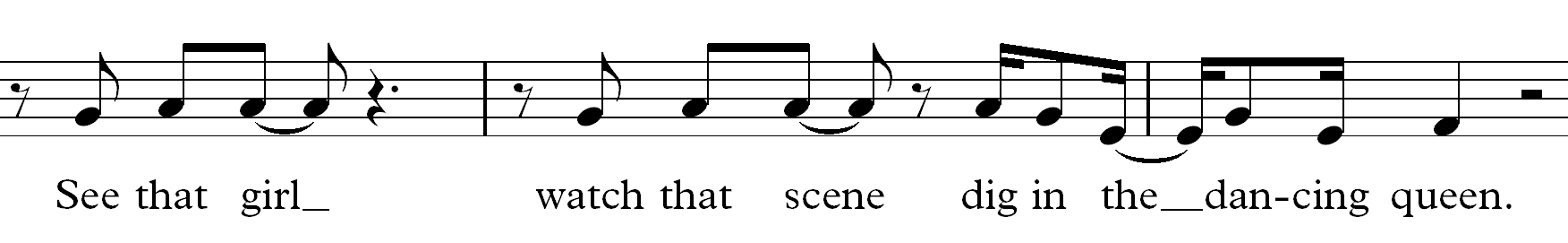

Mina's 'Bacio' is not the only quoted song in 'When I Was Cruel No. 2' which depicts a feminine presence. In the lyrics, the 'ghostly first wife' at the wedding implies that the bride of the song is a social climber by calling her a 'dancing queen', a direct allusion to ABBA's song of the same name. The ABBA quotation is more than merely textual: the form of the original melody is hidden in the song as well (see examples 2-3). Costello takes the melodic formation of ABBA but disentangles it from the original major tonic and uses the shape on the second and minor third (instead of seventh and high tonic of ABBA), lowering the final note of the phrase to the minor scale tonic (in F minor, G, A-flat, and descending to F). In this way, Costello takes the optimism of 'Dancing Queen' and transforms it intertextually into a contemptuous insult directed towards the bride, as well as a musical mark of pessimism. ABBA's upbeat party song has been queered to suggest cynicism and wantonness. |

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Example 2. Detail from ABBA's 'Dancing Queen' chorus. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Example 3. Detail from 'When I Was Cruel No. 2': the Dancing Queen allusion and melodic figure. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

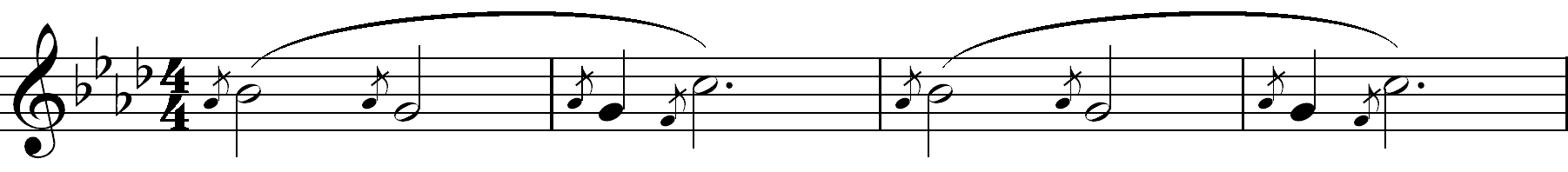

Erik Satie's Gnossienne No. 1 can also be heard in paraphrased form in Costello's song. (4:22-4:33 and 6:00-6:12; see examples 4-5.) Common features with Satie's music include satirical commentary on German (especially Wagnerian) art music. His music reveals a sense of parody, irony and frivolity, while avoiding emotional depth, fantastical subjects, or nostalgia.[27] Bryan R. Simms notes that the Gnossienne No. 1 contains 'witty marginalia', commenting on the frequent embellishments of the song.[28] John Richardson argues that the piece evokes such connotative meanings as exoticism, effeminacy and even camp aesthetics.[29] Costello quotes bars 20-24 of the Gnossienne No. 1: |

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Example 4: Bars 20-24 from Erik Satie's Gnossienne No. 1. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Example 5: Elvis Costello's version of Satie's Gnossienne No. 1 piano melody in 'When I Was Cruel No. 2'. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

An argument could be made that the song's instrumentation connects with gender roles in the song. The dream-like vibraphone and the paraphrased Satie piano melody seem to compliment Mina's voice. The vibraphone is heard in every chorus section, where the lyrics invariably refer to the bride; it is also the only part of the song where the harmonies shift from the steady flow of F minor, E flat major and B flat minor floating around the verses (to C minor,D flat, A flat, D diminished, D flat dim, E flat, and F open chord). Satie's Gnossienne No. 1 is not an accidental choice either; it brings to the song a sense of orientalist exoticism, 'faux naïveté' and effeminacy,[30] which connects with Mina's sampled voice on the track. The music creates a surreal atmosphere through the embellishment of the song with a piano melody in instrumental breaks and during verses with the same 'witty marginalia' of Gnossienne No. 1, creating a dream-like atmosphere, but also a continuation of Mina's sampled voice in the track and the similarly echoed vibraphone. When the paraphrased Gnossienne plays during the verses, they seem to comment on the bride: 'So she can dance her husband out on the floor/The captains of industry just lie there where they fall'. Otherwise the Satie paraphrase is heard in solo instrumental breaks, as a Leitmotif of sorts for the dancing bride. Therefore we can identify a trifold musical representation of the feminine: Mina's voice - the vibraphone - the Satie piano. |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contrasting with these instruments are the electric guitar and bass, both played by Costello, in addition to the original bass and guitar in Mina's song. Both of the added instrument sounds are manipulated with heavy effects. The bass, a Fender Six, at the beginning of the song employs a sidechain compression effect that creates a 'diving' feeling in the bass sound (frequently used in house music and dubstep). The added guitar sounds, played on a Ferrington Barytone and Silvertone Electric, are saturated with heavy distortion, tremolo effect and spring-reverb sound. Both instruments are also mixed to produce very little high-end sound, and elevated low and middle frequencies, creating a murky sound, which stands in diametric opposition to the very clear and precise sounds of the piano and vibraphone. This produces erotic frisson between the trifold feminine presence (Mina's voice - piano - vibraphone,) and the masculine presence of the sampler/ instrumentalist Costello, reflected in the grimy sounding instruments and the singer's voice. |

21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The connection between the song's bride and Mina's voice is uncanny; Costello depicts the yawning bride as sexually inviting, and indeed, we hear the 'un' syllable return rhythmically, again, suggesting a yawning noise. It is noteworthy that the 'un' appears on the last eighth note of the two-bar loop. The place is musically a little void, the breath before the next repetition implying space. Therefore her occupying this specific space can be heard as accentuating her presence in the song, up to the point of turning her into the idealised object of a male masochistic dream, in which the voice is perceived not purely as a sexual object but rather an adored one. Indeed, it might be the Cruel Lady's throne, her pedestal upon which Costello left (elevated) her.[31] The contribution of Satie's melody to this, as the extension of the feminine entity, is perhaps that of decadent camp aesthetics and performativity, implying not a factual state of affairs, but a certain playful interaction between the woman and the man of the song. |

22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gender roles have been problematized by scholars where looping techniques are concerned, especially during the early days of the technique. Ethical concerns arose in cases where the original voice on the track was left uncredited, but was instead viewed as arising from the artistic vision of the (usually male) sampling editor, making the voice (usually female) merely a creative resource for the sampler.[32] Costello does credit the original sample to Mina, but still we are invited to consider her position in the song; is she being dominated by Costello, or is she a dominatrix? Based on Barbara Bradby's writings, we could consider Costello's sample an effort to incorporate the female presence as the Other of the male author, something that can be moulded into any form or role as the male producer sees fit. Understanding this particular example in accordance with Bradby's text, we might additionally see it as an effort to suppress the powerful Italian singer by reducing her song's lyrics to the simple particle 'un' ('a', or 'one'). The result of this would be subjugating a singer who was a symbol of women's rights in highly patriarchal Italian society, where she became one of the first independent female artists in Italy. Her powerful rendering of songs and belting technique earned her the nickname 'la urlatore', the screamer or the howler, setting her voice apart from those of other, more traditional, classic bel canto female singers of the time[32a] The reduction of her elaborate vocal performance to a mere syllable sounded every two bars could be heard bringing about a loss of meaning in comparison to the original, leaving her muted by technology and entrapped within a repetitious cage. The reduction of her elaborate vocal performance to a mere syllable sounded every two bars could be heard bringing about a loss of meaning in comparison to the original, leaving her muted by technology and entrapped within a repetitious cage. |

23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

There is, however, another side to Costello's use of Mina's voice that ought to be taken into account. Rather than trying to silence or constrict Mina's voice, it is notable that her voice was included in the loop by Costello in the first place, untampered. In this way, he aestheticises it, even instrumentalises it. Furthermore, Costello does not sing on top of Mina's 'un' syllable during the song, apart from a few instances. It feels like Costello has paid painstaking attention to shaping his melody and lyric lines so that they do not interfere with Mina's rhythmic sound. In a few instances he even hurries or delays his lines, in interaction with Mina, audibly foregrounding her voice, rather than obscuring it with his own vocals. This becomes a valid point when considering surreal aesthetics and its tendency to fetishize isolated body parts. In this view, Mina's isolated vocal syllable becomes a fetish (audio) object that is repeated every eight beats. Dividing Mina's voice into mere snippets is reminiscent of surrealist (visual, male) artists exploring 'the release of violence and sexuality' in their works.[33] While the surreal tendency to dislocate women's body parts, placing them in another setting has been seen as a violent act towards women and femininity, it also serves as a fetishization technique, where the desired part of a woman is detached from the person. In this way, we can argue that leaving Mina's voice in Costello's song is an effort at both fetishizing and controlling the feminine presence in the song, but he does credit Mina as the original artist as well, allowing her agency as a singing subject. Her presence in the song can thereby be redeemed (at least partially) from being a sampled, dominated posthuman automaton to the driving force of the song; a dominatrix disciplining the beat. This interpretation is supported by the writing of Susana Loza, who criticises Bradby's theorization of sampled women as invariably dominated and repressed.[34] According to Donna Haraway's and Katharine Hayle's idea of cyborgian aesthetics, such robotic women can also be perceived as agentic and empowered.[35] Loza writes: |

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A cyborg diva melts binaries, crosses genders, slips into other species and genres, samples multiple sexualities, and destabilises dance music with her stammered replies. This cyborg's sexuality is a liquid loop, liberated yet situated by the circuit of its libidinal motions.[36] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The purpose of using the sampling technique in Costello's case may not, then, be (only) to repress or objectify the female voice, but to eroticize and fantasize, thereby making the effects of the original voice in the song more powerful. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

'When I Was Cruel No. 2' presents the relationship between the bride and 'I' quite vaguely, and the queer potential of their gender roles seems ambivalent at best: while the woman seems to hold most of the decisive power, she is more a fantasy than an actual being. From this standpoint, the masculine perspective of the song seems quite traditional as well. While the sexual power roles are ambiguous between the two, Costello reflects upon the situation with both fascination and scorn, creating a remarkable, obscure, even slightly neosurreal mixture of emotional states that runs throughout the music. It seems, then, that the queering of hegemonic masculinity happens somewhere else than in the construction of the feminine in the music and its relation to masculine elements. In the next section, I will consider more closely the feeling of melancholia that pervades both Costello's song and Sacher-Masoch's writings, which holds a important key to the new queer masculinities that are made possible in male masochistic fantasies. |

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The queer art of failure: Surreal melancholia and music |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Costello's 'When I Was Cruel No 2' manifests aspects of masochism that often go unnoticed in Sacher-Masoch's writings. While I cannot claim that Sacher-Masoch's texts are surreal, historically or otherwise, there is a tension between masochistic fantasy and reality that includes a bitter side, a disillusionment that is constantly disavowed and escaped from. Costello's song depicts a state of melancholy that is similar to Sacher-Masoch's world. Melancholy, as an aesthetic and cultural term, refers to a contradictory feeling where emotional pain is turned into pleasurable experience. It need not be only attached to human feelings; it can also apply to appreciation of the surrounding world or art. It is attached to such terms as sadness, ennui, Weltschmertz, and depression, but also beauty, joy, the sublime, and enjoyment.[37] This highly complex feeling is present also in Sacher-Masoch's Venus in Furs, where the protagonist Severin bitterly states: ''Be the anvil or be the hammer' are never more true than when applied to the relations between man and woman'.[38] The older Severin has decided to be the tyrant, but still recounts his story of Wanda with meticulous detail, revealing the manifold nature of melancholy: it is both suffering and pleasure, both poetic and psychological. Leo Bersani and Adam Phillips regard this pleasure as a masochistic one: |

26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

What masochism makes possible is the pleasure in pain; or rather what masochism reveals is the capacity to bear, the capacity to desire the ultimately overwhelming intensities of feeling that we are subject to. In this sense the masochistic is the sexual, the only way we can sustain the intensity, the restlessness, the ranging of desire.[39] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Listening to Costello's song from this angle, the relationship between 'I' and the bride is both bitter and eroticized. The looped voice of Mina follows the song as an ubiquitous force, while the 'I' position suggests a masochistic level of enjoyment in the obsessive attentiveness he pays to the bride. Comparing this to Costello's own voice, recorded very dryly and compressed, and his un-gimmicky performance with very little variation, the image of the bitter man of the song is reinforced. Throughout most of the song, Costello's voice is either disinterested and tart, or belted out bitterly. The exception to this is the very last verse (6:12-6:32; 'Look at me now / She's starting to yawn / She looks like she was born to it / Ah, but it was so much easier / When I was cruel'). Here Costello switches his voice to a softer mode of production, lingering in the rhythm of the words, and adding legatos to almost every melodic line. During most of the song, 'I' is assuming the role of the tyrant, the cruel one, but the last line reveals the singer subject's return to a tenderer, submissive state in relation to the woman and their relationship. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In a way, Costello's song depicts the same indifference and disillusionment as Sacher-Masoch's opening of Venus in Furs. But Costello's song is still filled with unattainable sensuality, longing and eroticism, ever present in the voice of Mina, who still lingers in the imagination of the 'I', who in turn, tries to cruelly convince himself that the fascination with the bride is indeed over. But, according to Deleuze, this is all in vain: in fact, the process of disillusionment and cruelty is at the heart of masochistic experience. Treating an object cruelly desexualises it, but it does not de-fetishize it. The fetish value, still apparent in the desexualised object of desire, by default re-sexualises it, making it possible for the masochistic hero to both hate and desire the object: 'the desexualised has become in itself the object for sexualisation'.[40] This is accentuated also in the tango-like rhythm of the song; reading the song as a traditional tango, where the lyrics often depict a man betrayed by a sexually wanton woman who uses her sexuality to climb societal ladders (very comparable to the high-society wedding Costello depicts), Marta E. Savigliano asserts that the tango is deeply enmeshed in themes of male impotence, cuckoldry, jealousy, and, to some extent, violence towards women.[41] Similarly to Deleuze's assertion, these men are bitter yet still fascinated; so it seems to be with Costello's song as well. |

27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Costello does not straightforwardly explain who occupies the 'I' position in the song. We cannot know for sure if he is the groom at the wedding, or perhaps a previous lover or husband of the bride, or just a general onlooker. We can however hypothesise that there is some history between the 'I' and the bride. The gossiping guests paraphrase the bride's past, and the very name of the song, 'When I was cruel,' implies previous history. Costello's previous version of the song, 'When I Was Cruel' (2002b), which perhaps could be referred to as the 'No. 1' version for the purposes of this analysis, is distinctly different to the 'No. 2' in its atmosphere, music, arrangement and lyrics. Costello published 'Cruel No. 1' on the album Cruel Smile (2002), which contains B-sides, live recordings and leftover material from the album When I Was Cruel. In the lyrics of 'No. 1', we find another relationship depicted: the 'you' of the relationship has apparently been running away, and perhaps philandering (note the euphemism, 'did someone flip your switch?') while running from the 'I' of the song. The mocking 'I' depicts their relationship: |

28 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

You talk your way out of this, did someone flip your switch? |

|

|

|

Now there is only right or wrong, can you tell which is which? |

|

|

|

But it was so much easier, when I was cruel |

|

|

|

(Costello: 'When I Was Cruel', 2002b.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first lyrics appear after an 'introduction' of a noisy crescendo cluster from a Hammond organ, spontaneously switching to the opening to the song. This creates an element of surprise, Costello's voice leaping out of the incoherent shadows, almost as if he were stalking the 'you'. There is an air of condescension in the lyrics, with the 'I' mocking and pleading for an explanation for the behaviour of 'you'. The major key of the song and the simple melody seem to make the lyrics sound almost juvenile, or perhaps more accurately, patronizing. However, there is a feeling of SM-erotica hiding as jealousy in the lyrics: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oh when I was cruel and I could make you very sorry |

|

|

|

Lonely cowards followed me like ghouls |

|

|

|

And you liked me too, When I was cruel |

|

|

|

Oh you know you did, When I was cruel |

|

|

|

(Costello: 'When I Was Cruel', 2002b.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It seems that the relationship was built around performative cruelty, which was also suggested to be enjoyed by 'you'. There is an air of coercion about these lyrics, a libertine-sadistic pleasure in debauchery and degradation.[42] One could even argue that the 'you' had sexual adventures outside the primary relationship, as is often the case also in the tango tradition,[43] or that the relationship involved cuckolding and mock punishments. The distinction between 'Cruel No. 1' and 'Cruel No. 2' is thus marked. While the 'I' of the first 'Cruel' seems to be, indeed, enjoying the performative cruelty coming from both sides of the relationship, in the second 'Cruel' this apparent pleasure is not as straightforward. Some disillusionment has taken place between the songs: 'I' of 'No. 2' spends a lot of time observing the bride, depicting her body and scent, finding it a bitter pleasure. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Through disillusionment we also arrive at the theme of failure. Queer theorist Judith Halberstam argues in The Queer Art of Failure that often the cruel flipside of everyday optimism is left unnoticed: when optimism is seen as the main measure of success in life, marriage and even health, the opposite of these, divorce, sickness, or death, are seen as the deficiency or failure of an individual. Halberstam sees failure as a queer form of being, precisely because of the normativity inscribed in optimism and success: '[f]ailing is something queers do and have always done exceptionally well [...] If success requires so much effort, then maybe failure is easier in the long run and offers different rewards.'[44] |

29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Costello's song describes failure in the context of perhaps the most culturally optimistic situation possible: a wedding. By evoking a more nihilistic perspective of the event and envoicing this statement through surreal and even somehow grotesque instrumentation, the atmosphere is a long way away from Wagner's wedding march so ironically referenced in the first verse lyrics ('Here comes the bride'; 1:01-1:05). Instead of celebrating this union, it is pointed out that at least three different divorces have preceded it, and even these previous wives linger as guests at the wedding, one of them openly mocking the bride. Costello creates a wedding dystopia, where optimism only thinly, if at all, veils failure and bitterness. Instead of being rewarded for success in this marriage, interpreting events through the ideas of Halberstam suggests childishness, loss, masochism and passivity, and modes of unbecoming as the alternative rewards of failure.[45] While Halberstam's readings of masochism are related to femininity and feminism, in Costello's case, we can argue that male masochism is at the root of the pleasure taken in failure. Leo Bersani theorises masochism as self-shattering, a slight differentiation from the Freudian death drive.[46] Bersani argues that sexuality constitutes |

30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

a kind of psychic shattering, [...] a threat to the stability and integrity of the self - a threat which perhaps only the masochistic nature of sexual pleasure allows us to survive.[47] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This shattering, Bersani thinks, is at the heart of sexuality itself, calling it the 'masochistic jouissance'[48] where pleasure is found in dissolving of the boundaries of ego, and 'rediscovering the self outside the self'.[49] All power, and by extension, all responsibility, has been taken away from the self, and so the self takes pleasure in adopting the role of a victim of circumstance in order to survive, rather than suffering victimhood as a personal failure. The experience is thus also that of narcissism, of escaping responsibility. Considering this, the queer art of failure here is to realize, through masochism, that failure is not a personal fault. If there is no self, then the self has no blame in not finding success. Instead, the shattered self finds pleasure in pain, makes sense out of nonsense, pleasure in displeasure, and eroticism in cynicism. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I therefore argue that this multihued experience is, in essence, a neosurrealist one: the song contains coexisting realities and fantasies, and opposed yet simultaneous strong feelings within the same frame. Thus the concepts of success and failure are mixed together to form new, neosurreal, thought-provoking meanings. Perhaps, in Costello's song, the very pleasure of failure comes by means of prolonging the song through subjective temporality and revelling in this melancholic feeling, where the social 'success' of marriage is already recognised as a failure at the wedding. The very moment of this realisation is extended throughout the song, with Mina's suspended mocking repeatedly heard in the background, and the masochistic enjoyment is to lose yourself in the music, in the affectivity of the song, which still manages to be a beautiful song despite its subject and Costello's dystopic handling of it. |

31 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conclusion: Envoicing the fantastical lady and queer masculinities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Elvis Costello's 'When I Was Cruel No. 2' is, in my reading, a multihued expression of male masochism, mixed with darker hues of disillusionment, bitterness and failure. While the sampled song is a depiction of a high-society wedding, it also creates a specific kind of eroticism based on negative feelings of melancholy and nostalgia. The question still remains, however, as to how Costello's song constructs queer spaces for both the female presence of the song and new masculinity codes established through this non-normative set of affairs, where the sovereign Lady controls the doting man. Can we call this set of affairs truly 'queer'? Does the masochistic relationship create any new queer ways of being? |

32 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

It could be easily suggested that the male masochist has all agency and control, and the Lady is seemingly there only to fulfil his fantasy. Supporting this, almost all sources discussing sadomasochistic relationships claim that the submissive is the one with ultimate control; even Foucault[50] argues, albeit in a more general sense, that power comes from below. What makes this specific situation non-queer, then, is the thought of male over female power. If the male heterosexual masochistic fantasy is only thinly veiled male power exerted over the female, the subversive potential of the scenario is questionable. Seemingly, the man would use the woman only for his entertainment, and again, the woman would be controlled, not the one in control. Indeed, if we see the woman in this power dynamic as the ultimate fetish object, the woman's agency is debatable. After all, '[a] fetish can be held, seen, smelled, even heard if it is shaken, and most importantly it can be manipulated at the will of the fetishist'.[51] In this case, the masochistic man's relinquishing of power becomes an 'elaborate reversal of gender agency, but not of gender identity'.[52] |

33 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Comparing this to Costello's song, the presence of Mina's voice is also both fetishised and appreciated. Costello does manipulate the feminine presence in the song, quite literally with technology and music sampling. It is not, however, a straightforwardly narcissistic and/or fetishistic endeavour: Costello grants Mina audible space (albeit, the space he chooses), allowing her sampled 'un' syllable to drive the song onwards and not obscuring it with his own whenever possible. Similarly, she becomes ubiquitous in the song, and creates an altered sense of temporality through the repetition of her voice, implying the past, present and future simultaneously. This is, again, at the heart of the masochistic experience, where losing yourself, making reality into fantasy[53] or shattering the boundaries of the ego[54] create a strong fantastical pleasure. |

34 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then again, looking at the feminine presence in the song, it cannot be denied that on some level, it is marginalised. Musicologist Ian Biddle's reading of male singer-songwriters and their 'new masculinity' formed around questions of vulnerability and intimacy, states that while this 'new' masculinity toys with the 'danger' or awareness of potential hurt, it still does not challenge gender normativity or traditional tropes of hegemonic masculinity. Indeed, Biddle suggests that one of the ways to test this new masculinity is to weigh it against the represented femininity in these songs. Biddle writes: |

35 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

She is addressed, but is all but silenced; zombielike backing vocals, over-spectacularized ('artificial' overtrained) voice or crude anonymous cipher of a 'vulnerability' (one's 'feminine' side), she is always disciplined into the margins, always held in a tight discursive grip at the service of masculine authenticity.[55] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Similarly to this, Costello is seen to create a controlled, marginal presence for the female vocals in the song through the sampled voice of Mina. While I could argue, like Biddle, that the song includes a disciplined presence auditively, it is also true that the (sexual) masochistic fantasy rotates around the woman as well. Without the Lady, there is no masochistic dream, nor is there an alternative masculinity. Framing the song with masochistic aesthetics reveals the importance of the woman, not as abject, but rather idolised Other. It is, however, a matter of debate whether the Othered Lady still is a human entity, equal with other wielders of power, or an empty fetish symbol for masochistic men to utilize as they please. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As in all power relationships, the submissive man gives the Lady's power to her from below. Mina's omnipresent voice, looped by Costello, maintains its position as center of attention throughout 'When I Was Cruel No. 2', also existing outside of the song. Therefore, removing the submissive man from the picture does not automatically mean that there is no sexually empowered woman; the only image disappearing is the symbol of the Lady in the masochistic imagination. Mina's voice still remains an empowered, strong entity. Whether we can consider this state of affairs 'sexist' remains a matter for debate. Lynda Hart claims that '[a]ll our sexualities are constructed in a classist, racist, heterosexist, and gendered culture, and suppressing or repressing these fantasy scenarios is not going to accomplish changing that social reality'.[56] While I would not dispute this statement, the opposite might also be stated: embracing and celebrating these fantasy scenarios based on a classist, racist, heterosexist, and gendered culture will also not change the social reality that spawned these fantasies, parodied or not. |

36 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Returning to McClintock's claim of male masochism as a reversal of gender agency but not of gender identity, I would like to contest it somewhat. There are multiple ways to approach the matter of alternative masculinities in the masochistic fantasy, as depictions of masculinity vary from musical genre to genre. One is through the concept of vulnerability, usually abjected in normative heteromasculinity. Sarah F. Williams writes of emo rock (emotionally oriented rock) as trying to 'reconcile the long-established codes of masculinity - musical representations of aggression, pomp, stoicism, misogyny, and determination - with more multifaceted human expressions of heartache, weakness, longing, and loss'.[57] Emo accomplished this with more lush instrumentation, complex harmony arrangements and lyrical content, where the collective fears and anxieties of the (especially teenager) audiences are negotiated. Shana Goldin-Perschbacher on the other hand theorises singer-songwriter Jeff Buckley's performances as 'unbearable intimacy', where his 'vulnerable-sounding voice and penchant for singing women's songs in a female vocal range' are considered as Buckley's 'transgendered vocality'.[58] Buckley's voice and emotional delivery effectively queers his artistic persona into a new vocal sphere, where his embodied masculinity is in discourse with his delivery akin to female artists' voices and emotionality. In both these articles, the crisis of masculinity negotiated in music relates to questions of artistry, poetry, and emotional vulnerability. |

37 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Costello's 'When I Was Cruel No. 2' explores vulnerability in a complex way. The song may be a depiction of disillusionment and bitterness, but the masochistic mindset still remains vulnerable to the power of the fetishized woman. Indeed, the bitterness and disavowal expressed by the singer towards the woman reveal vulnerability still apparent in the erotic experience, tainted as it may be by melancholia. There is also a difference between emo rock artists and Costello; mainly, age. Emo suggests juvenile feelings, and vulnerability is always a part of growing from boy to man: 'Boys are volatile, unpredictable and vulnerable. [...] His vulnerability is made more acute by his own recklessness and spontaneity.'[59] In contrast, Costello was 47 years old when he released the album on which 'When I Was Cruel No. 2' appears. His vulnerability is perhaps not as obvious as the emo rockers, or any younger man/boy singers. |

38 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

All in all, Costello's song demonstrates some potential for queer masochism but still remains in an ambivalent state, much as debates about (male) masochism and sadomasochism in general. To argue that bracketing this fantasy as precisely such a fantasy, regardless of existing gender power imbalances that are still rampant in society at large and the music business, is not to erase the problematic aspects of this fantasy. Paraphrasing one of the most prolific pro-SM feminists, Gayle Rubin's words,'there's nothing inherently feminist or non-feminist about S/M',[60] I propose a similar formulation: ultimately, there's nothing inherently queer or non-queer about SM or male masochism in an ontological or epistemological sense. There is queer potential, but to ignore the problematic sides of male masochism is to miss out perhaps on the specific pleasures of it; eroticizing a social taboo seems to be a large part of the enjoyment, which does not imply accepting the taboo in general. |

39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

What of queer sounds and spaces then? I argue that alternative sexual pleasures can be created and negotiated in musical pieces by precisely creating a musical space, similar to a fantasy or a dream, in which the pleasures are explored and even fetishized. Listening for queer sounds can contribute to our understanding of how queer genders or sexualities are created. As such, thinking about music through the concepts of 'space' and 'sound' proves to be an invaluable addition when discussing 'queerness' in music and musicology.

Notes [1] See especially Nikki Sullivan, Critical Introduction to Queer Theory (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), 158-159. [2] Gillez Deleuze, ‘Coldness and Cruelty’, Masochism (New York: Zone Books, 2006 [1989, 1967]), 9-138; Leo Bersani, Is The Rectum A Grave? And Other Essays (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2010); Leo Bersani, The Freudian Body: Psychoanalysis and Art (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986). [3] Anna-Elena Pääkkölä, Sound Kinks: Sadomasochistic Erotica in Audiovisual Music Performances. Annales Turkuensis B: 422, doctoral dissertation (Turku: University of Turku, 2016). [4] Richard Middleton, ‘Introduction: Music Studies and The Idea of Culture’, in Clayton, Martin, Trevor Herbert & Richard Middleton (eds.), The Cultural Study of Music: A Critical Introduction (New York: Routledge, 2012 [2003]), 1-14; John Richardson, An Eye for Music: Popular Music and The Audiovisual Surreal (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012); Alistair Williams, Constructing Musicology (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009 [2001]). [5] Judith A. Peraino, Listening to the Sirens: Musical Technologies of Queer Identity from Homer to Hedwig (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006); Elizabeth Wood, ‘Sapphonics’, in Brett, Philip, Elisabeth Wood & Gary C. Thomas (eds.), Queering The Pitch (New York: Routledge, 2006 [1993]), 27-66. [6] See especially Mieke Bal, Travelling Concepts in the Humanities: A Rough Guide (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002); John Richardson, ‘Closer Reading and Framing in Ecocritical Music Research’, in Feller, Gerlinde, and Birgit Abels (eds.), Music Moves: Exploring Musical Meaning Through Spatiality, Difference, Framing and Transformation. Göttingen Studies in Music vol. 6 (Hildesheim: Olms, 2016a), 157-193; John Richardson, ‘Ecological Close Reading of Music in Digital Culture’, in Abels, Birgit (ed.), Embracing Restlessness: Cultural Musicology, Göttingen Studies in Music, vol. 5 (Hildesheim: Olms, 2016b) 111-142. [7] Tor Christensen, ‘Costello Gets Back in Touch with His Inner Angry Young Man’, Daily Camera 2002, http://www.elviscostello.info/articles/d-g/daily_camera.020531a.html (23.9.2015). [8] Simon Frith, Performing Rites: Evaluating Popular Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 171. See also Elvis Costello, Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink (New York: Viking, 2015), 573, 580-581. [9] Luis-Manuel Garcia, ‘On and On: Repetition as Process and Pleasure in Electronic Dance Music’, Music Theory Online, Vol. 11, No. 4 (2005), http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/ mto.05.11.4/mto.05.11.4.garcia.html (7.9.2015), 3.1, 6.1. [10] Deleuze, ’Coldness’; Gillez Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, tr. Paul Pattion (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994 [1964]). [11] Deleuze, ’Coldness’, 70-72. [12] See Kanshi H. Sato, ‘Sacher-Masoch, Pélanda and Fin-de-siècle France’, Waseda Global Forum 7 (2010), 339-362: 345. [13] Deleuze, ‘Coldness’, 71. [14] Stan Hawkins, ‘Feel the Beat Come Down: House Music as Rhetoric’, in Moore, Allan F. (ed.), Analyzing Popular Music (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009 [2003]), 80-102: 101; Walter Hughes, ‘In the Empire of The Beat: Discipline and Disco’, in Ross, Andrew & Tricia Rose (eds.), Microphone Fiends: Youth Music & Youth Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994), 147-157: 153; John Richardson, Singing Archaeology: Philip Glass’s Akhnaten (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1999), 54-57. [15] Bersani, Is the Rectum a Grave, 174. [16] Ibid. 71. [17] Deleuze, ’Coldness’, 115. [18] See Richardson 1999; Garcia 2005. [19] Sigmund Freud, Beyond The Pleasure Principle, tr. C. J. M. Hubback (Mansfield Centre: Martino Publishing, 2009 [1911]), 1. [20] Ibid. 54; see also ibid. 59. [21] Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and The Death Drive (London: Duke University Press, 2004), 25. [22] Ibid. 25. [23] Bersani, The Freudian Body, 39. [24] Hawkins, ’Feel the Beat’, 101. [25] Jeremy Gilbert and Ewan Pearson, Discographies: Dance Music, Culture and the Politics of Sound (New York: Routledge, 1999), 101. [26] John Richardson, ‘'Black and White' Music: Dialogue, Dysphoric Coding and The Death Drive in The Music of Bernard Herrmann, The Beatles, Stevie Wonder and Coolio’, in Heinonen, Yrjö, Tuomas Eerola, Jouni Koskimäki, Terhi Nurmesjärvi & John Richardson (eds.), Beatlestudies 1: Songwriting, Recording, and Style Change (Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 1998), 164-167. [27] Richard Taruskin, Music in The Early Twentieth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 65, 566, 569-570. [28] Bryan Simms, Music of The Twentieth Century: Style and Structure (Belmont: Schirmer, Cengage Learning, 1996 [1982]), 175. [29] Richardson, An Eye for Music, 132-133. [30] Ibid. 132. [31] See Slavoj Žižek, ‘From Courtly Love to Crying Game’, New Left Review a. Vol. 202 (1993), 95-96. [32] Barbara Bradby, ‘Sampling Sexuality: Gender, Technology and The Body in Dance Music’, Popular Music Vol. 12, No. 2 (1993), 155-176: 161, 169. [32a]Paulo Prato, 'Virtuosity and Populism: The Everlasting Appeal of Mina and Celentano', in Fabbri, Franco, and Goffredo Plastino (eds.), Made in Italy: Studies in Popular Music (New York: Routledge, 2014), 162-171: 162, 166, 169. [33] Maureen Turim, ‘The Violence of Desire in Avant-Garde Films’, in Petrolle, Jean, and Virginia Wright Wexman (eds.), Women and Experimental Filmmaking (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 71-90: 73. [34] Susana Loza, ‘Sampling (Hetero)Sexuality: Diva-Ness and Discipline in Electronic Dance Music’, Popular Music Vol. 20, No. 3 (2001): 349-357. [35] Donna Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991), 163; Katharine N. Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999), 7, 13. [36] Loza, ’Sampling (Hetero)sexuality’, 350-351. [37] See Julia Kristeva, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia, tr. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989 [1987]); Slavoj Žižek, ‘Melancholy and the Act’, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 26, No. 4 (2000), 657-681. [38] Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, Venus in Furs, in Masochism (New York: Zone Books, 2006 [1989, 1870]), 150. [39] Leo Bersani and Adam Phillips, Intimacies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 94. [40] Deleuze, ’Coldness’, 117; 116-118. [41] Marta E. Savigliano, ‘Whiny Ruffians and Rebellious Broads: The Tango as a Spectacle of Eroticized Social Tension’, Theatre Journal, Vol. 1, No. 47 (1993), 94-95. [42] See Deleuze, ’Coldness’, 18-19. [43] See Savigliano, ‘Whiny Ruffians’, 87, 93-94. [44] Judith Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Durnham: Duke University Press, 2011), 3. [45] Ibid. 23. [46] Bersani, The Freudian Body, 41, 60-64. [47] Ibid. 60. [48] Ibid. 49. [49] Bersani, Is the Rectum a Grave, 175. [50] Michel Foucault, History of Sexuality: Volume One, The Will to Knowledge, tr. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage, 1998 [1976]), 94-96. [51] Louise J. Kaplan, Cultures of Fetishism (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 5, emphasis mine. [52] Anne McClintock, ‘Maid to Order: Commercial Fetishism and Gender Power’, Social Text (1993), 87-116: 97. See also Steven P. Schacht and Lisa Underwood, ‘The Absolutely Fabulous but Flawlessly Customary World of Female Impersonators’, Journal of Homosexuality Vol. 46 No. 3-4 (2008), 1-17. Here the writers make a similar point to female impersonators who achieve a classic position of masculine power by seeming to defer that power. [53] Deleuze, ‘Coldness’, 72, [54] Bersani, The Freudian Body, 60. [55] Ian Biddle, ‘'The Singsong of Undead Labor': Gender Nostalgia and The Vocal Fantasy of Intimacy in The 'New' Male Singer/Songwriter’, in Jarman-Ivens, Freya (ed.), Oh Boy! Masculinities and Popular Music (London: Routledge, 2007), 125-144: 141. [56] Lynda Hart, Between the Body and the Flesh: Performing Sadomasochism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 33. [57] Sarah F. Williams, ‘'A Walking Open Wound': Emo Rock and The 'Crisis' of Masculinity in America’, in Jarman-Ivens, Freya (ed.), Oh Boy! Masculinities and Popular Music (London: Routledge, 2007), 145-160: 145, 153. [58] Shana Goldin-Perschbacher, ‘'Not with You But of You': 'Unbearable Intimacy' and Jeff Buckley’s Transgendered Vocality’, in Jarman-Ivens, Freya (ed.), Oh Boy! Masculinities and Popular Music (London: Routledge, 2007), 213-233: 213. [59] Germaine Greer, The Beautiful Boy (London: Thames & Hudson, 2006 [2003]), 21. [60] Gayle Rubin, Deviations: A Gayle Rubin Reader (London: Duke University Press, 2011), 126.

Bibliography Abels, Birgit (ed.), Embracing Restlessness: Cultural Musicology, Göttingen Studies in Music, vol. 5 (Hildesheim: Olms, 2016). Bal, Mieke, Travelling Concepts in the Humanities: A Rough Guide (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002). Bersani, Leo, The Freudian Body: Psychoanalysis and Art (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986). ------ Is The Rectum A Grave? And Other Essays (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2010). Bersani, Leo and Adam Phillips, Intimacies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008). Brett, Philip, Elisabeth Wood & Gary C. Thomas (eds.), Queering The Pitch (New York: Routledge, 2006 [1993]). Clayton, Martin, Trevor Herbert & Richard Middleton (eds.), The Cultural Study of Music: A Critical Introduction (New York: Routledge, 2012 [2003]). Costello, Elvis, Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink (New York: Viking, 2015). Deleuze, Gillez, Difference and Repetition, tr. Paul Pattion (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994 [1964]). Edelman, Lee, No Future: Queer Theory and The Death Drive (London: Duke University Press, 2004) Feller, Gerlinde and Birgit Abels (eds.), Music Moves: Exploring Musical Meaning Through Spatiality, Difference, Framing and Transformation. Göttingen Studies in Music vol. 6 (Hildesheim: Olms, 2016). Foucault, Michel, History of Sexuality: Volume One, The Will to Knowledge, tr. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage, 1998 [1976]). Freud, Sigmund, Beyond The Pleasure Principle, tr. C. J. M. Hubback (Mansfield Centre: Martino Publishing, 2009 [1911]). Frith, Simon, Performing Rites: Evaluating Popular Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998). Gilbert, Jeremy and Ewan Pearson, Discographies: Dance Music, Culture and the Politics of Sound (New York: Routledge, 1999). Greer, Germaine, The Beautiful Boy (London: Thames & Hudson, 2006 [2003]). Halberstam, Judith, The Queer Art of Failure (Durnham: Duke University Press, 2011). Hart, Lynda, Between the Body and the Flesh: Performing Sadomasochism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998). Haraway, Donna, Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991). Hayles, Katharine N., How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999). Jarman-Ivens, Freya (ed.), Oh Boy! Masculinities and Popular Music (London: Routledge, 2007). Kaplan, Louise J., Cultures of Fetishism (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006). Kristeva, Julia, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia, tr. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989 [1987]). Moore, Allan F. (ed.), Analyzing Popular Music (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009 [2003]). Peraino, Judith A., Listening to the Sirens: Musical Technologies of Queer Identity from Homer to Hedwig (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006). Petrolle, Jean and Virginia Wright Wexman (eds.), Women and Experimental Filmmaking (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005). Prato, Paulo, 'Virtuosity and Populism: The Everlasting Appeal of Mina and Celentano', in Fabbri, Franco, and Goffredo Plastino (eds.), Made in Italy: Studies in Popular Music (New York: Routledge, 2014), 162-171. Richardson, John, Singing Archaeology: Philip Glass’s Akhnaten (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1999). ------ An Eye for Music: Popular Music and The Audiovisual Surreal (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). Ross, Andrew and Tricia Rose (eds.), Microphone Fiends: Youth Music & Youth Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994). Rubin, Gayle, Deviations: A Gayle Rubin Reader (London: Duke University Press, 2011). Simms, Bryan, Music of The Twentieth Century: Style and Structure (Belmont: Schirmer, Cengage Learning, 1996 [1982]). Sullivan, Nikki, Critical Introduction to Queer Theory (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007). Taruskin, Richard, Music in The Early Twentieth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010). Williams, Alistair, Constructing Musicology (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009 [2001]). |

40

|